The IRS Is Still Coming for You, Offshore Tax Cheats

Amnesty program to end Sept. 28, but agency’s broader crackdown on evasion will go on

Hiding money from the U.S. government is a lot harder than it used to be.

On Sept. 28, the Internal Revenue Service will end its program allowing American tax cheats with secret offshore accounts to confess them and avoid prison. In a statement, the IRS said it’s closing the program because of declining demand.

But the agency vowed to keep pursuing people hiding money offshore and said it will offer them another route to compliance.

What a difference a decade makes.

Before 2008, an American citizen could often walk into a Swiss bank, deposit millions of dollars, and walk out confident that the funds were safe and hidden from Uncle Sam, says Mark Matthews, a lawyer with Caplin & Drysdale who formerly headed the IRS’s criminal division.

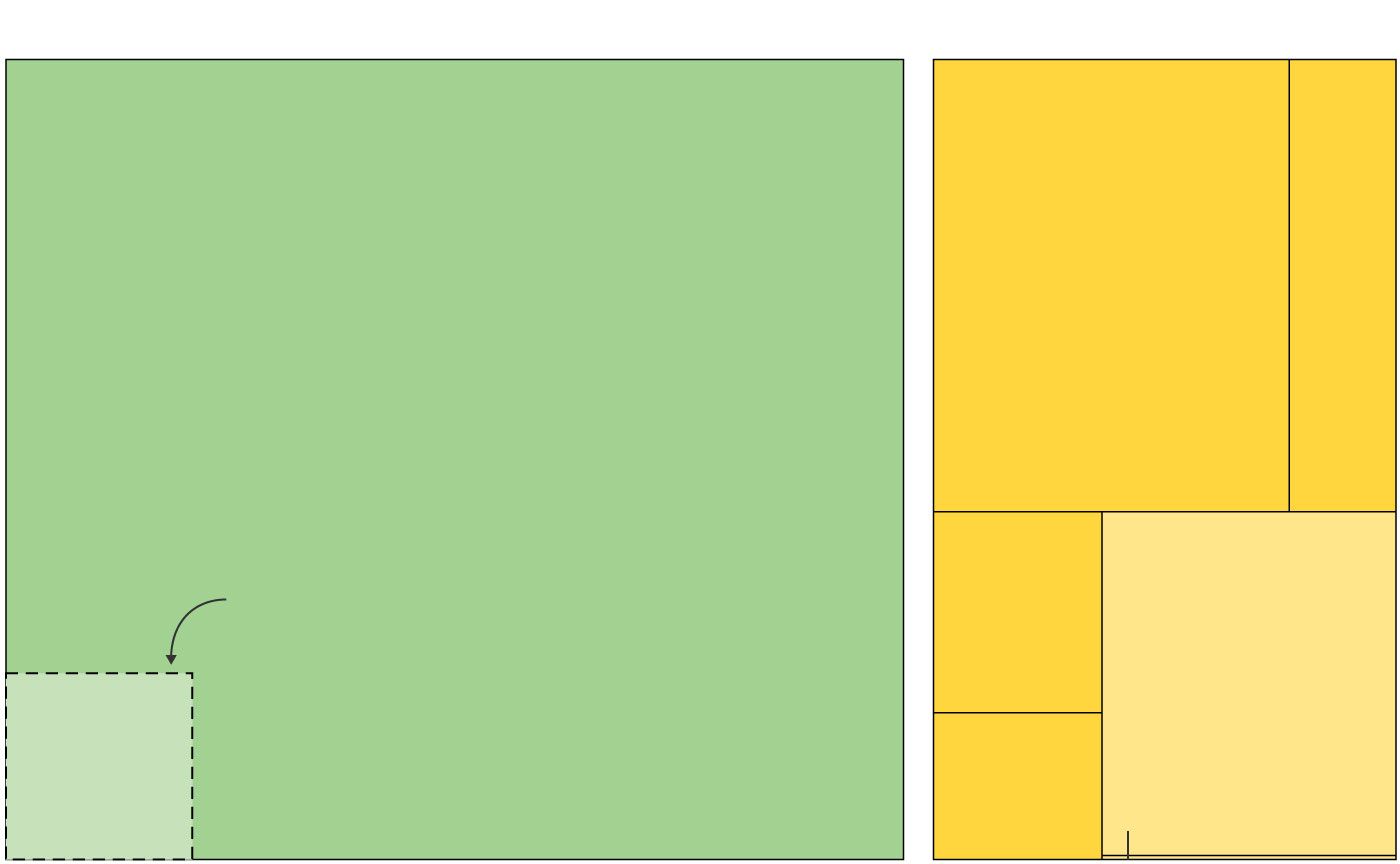

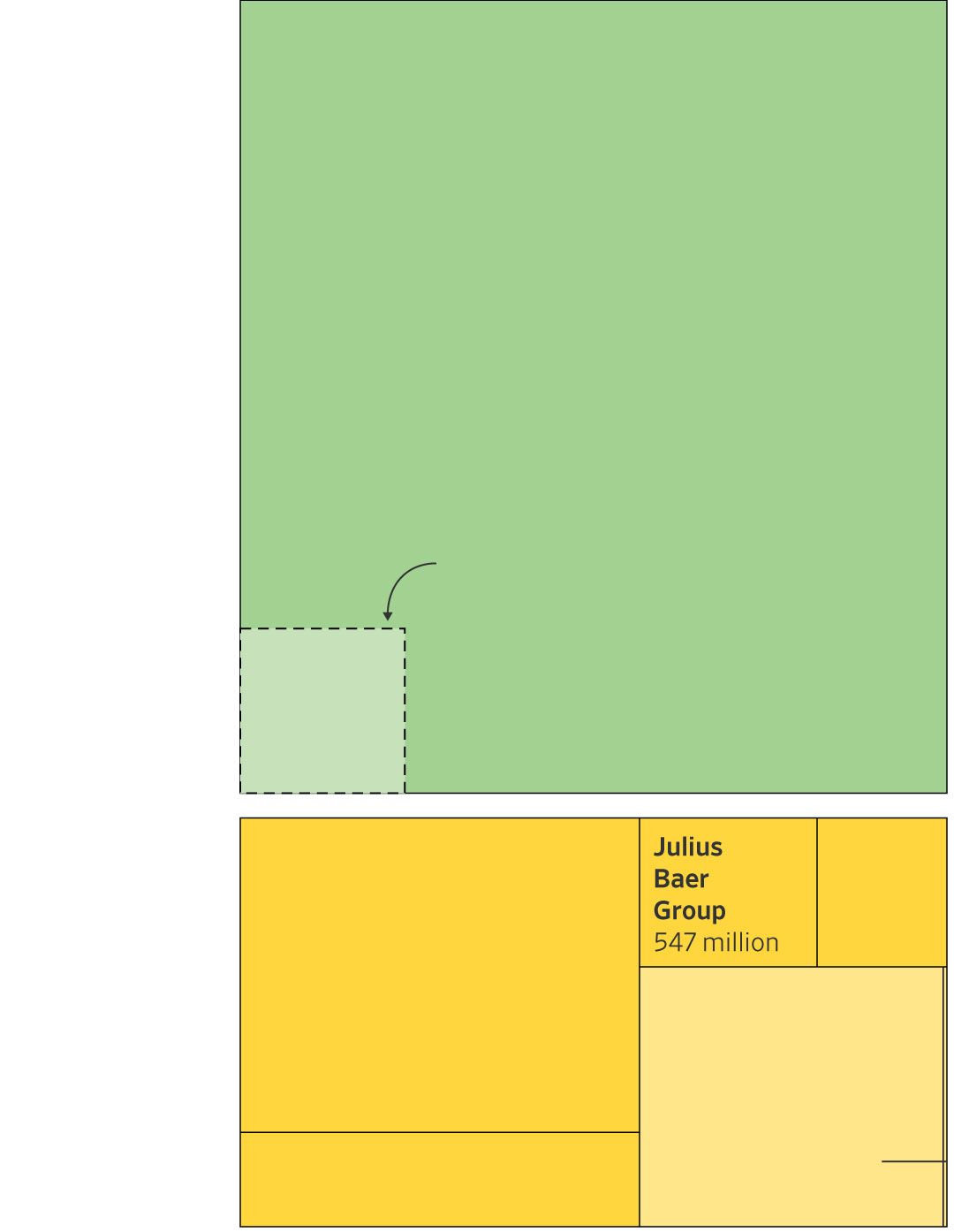

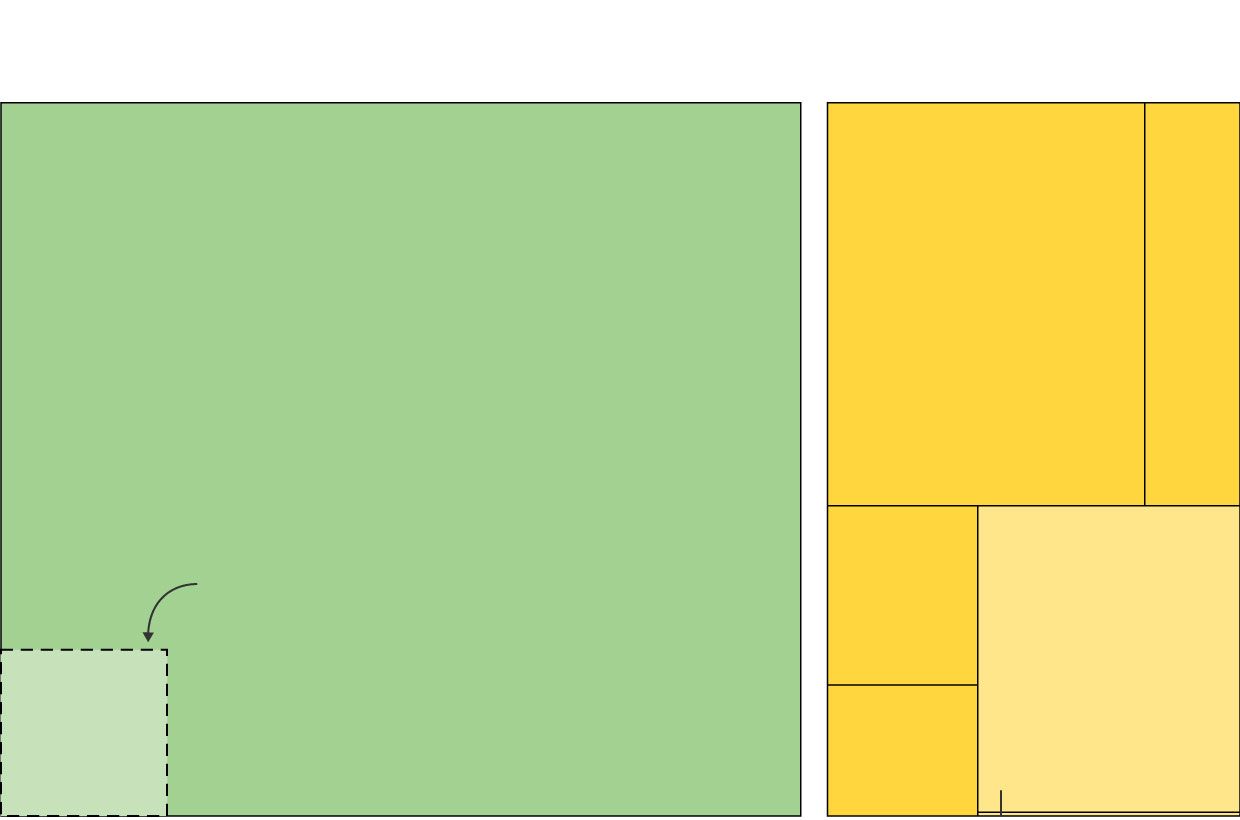

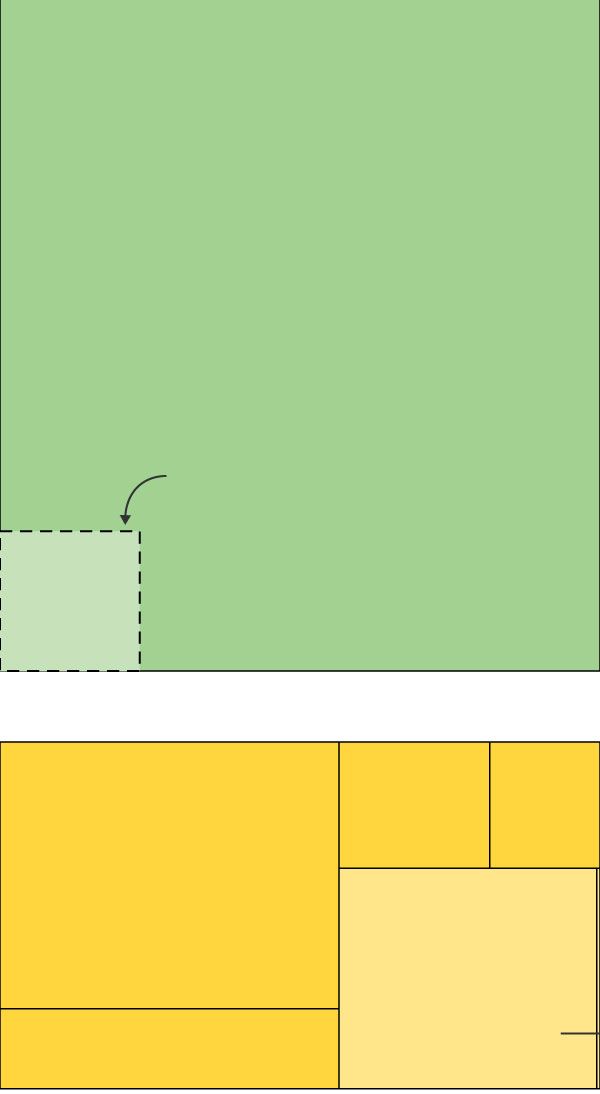

Hidden Treasure

Since 2008, U.S. officials have reaped more than $17 billion from cracking down on secret offshore accounts.

Amounts paid by individuals...

Amounts paid by institutions...

UBS

780

million

Credit Suisse Group

$2.6 billion

...from the IRS's limited-amnesty program

$11.6 billion

Other banks

1.6 billion

Julius

Baer

Group

547 million

including at least $500 million in connection with criminal prosecutions

Bank

Leumi

Group

400 million

Asset managers

19.94 million

Amounts paid

by individuals...

...from the IRS's limited-amnesty program

$11.6 billion

including at least $500 million in connection with criminal prosecutions

Amounts paid by institutions...

Bank

Leumi

Group

400 mil.

Credit Suisse Group

$2.6 billion

Other banks

1.6 billion

Asset managers

19.94 million

UBS

780 million

Amounts paid

by individuals...

Amounts paid by institutions...

UBS

780

mil.

...from the IRS's limited-amnesty program

$11.6 billion

Credit Suisse Group

$2.6 billion

Julius

Baer

Group

547 mil.

Other banks

1.63 bil.

including at least $500 million in connection with criminal prosecutions

Bank

Leumi

Group

400 mil.

Asset managers

19.94 mil.

Amounts paid by individuals from

the IRS's limited-amnesty program

$11.6 billion

including $500 million in connection with criminal prosecutions

Amounts paid by institutions...

Julius

Baer

Group

$547 million

Credit Suisse Group

$2.6 billion

Bank

Leumi

Group

$400 mil.

Other banks

$1.63 billion

UBS

$780 million

Asset managers

$19.94 million

Sources: Department of Justice; Internal Revenue Service (limited amnesty)

Now, he says, “Americans hiding money abroad have to go to small islands with sketchy advisers and less reliable financial systems.”

The reason: a historic crackdown on the longstanding problem of U.S. taxpayers hiding money offshore. U.S. officials ramped it up after a whistleblower revealed that some Swiss banks saw U.S. evasion as a profit center and were sending bankers onto U.S. soil to hunt for clients.

The defining moment came in 2008, when Justice Department prosecutors took Swiss banking giant UBS AG to court and managed to pierce the veil of Swiss bank secrecy. In 2009, UBS agreed to pay $780 million and turn over information on hundreds of U.S. customers to avoid criminal prosecution.

The Justice Department repeated the UBS strategy, with variations, for scores of other banks and financial firms in Switzerland, Israel, Liechtenstein and the Caribbean. So far, institutions have paid about $6 billion and turned over once-sacrosanct customer information. Major settlements are still to come.

Prosecutors also successfully pursued more than 150 individuals hiding money abroad. Some defendants earned jail time, and many paid dearly—a total of more than $500 million so far. Dan Horsky, a retired business professor and startup investor, appears to have handed over the largest amount: $125 million for hiding more than $220 million offshore.

“ More than ever, there’s no place to hide. ”

In many cases, a taxpayer can owe a penalty of half a foreign account’s value, if it’s greater than $10,000 and it’s not reported to the Treasury Department. Ty Warner, the billionaire creator of Beanie Babies plush toys, paid $53.6 million for hiding an account with more than $100 million.

The IRS capitalized on tax cheats’ fears of detection with its Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program, the limited amnesty that’s ending. It hit confessors with large penalties in exchange for no prosecution. Since 2009, more than 56,000 U.S. taxpayers in the program have paid $11.1 billion to resolve their issues.

To be sure, the U.S. crackdown hasn’t reached everywhere—notably Asia.

Edward Robbins, a criminal tax lawyer in Los Angeles formerly with the IRS and Justice Department, attributes the enforcement gap to the widespread use of human beings, rather than structures like trusts, to shield account ownership in Asia.

“In the Far East, individuals often use other individuals who use other individuals to hold assets. Finding the true owner is a tough nut to crack, unlike in the West,” he says.

More Tax Report

The crackdown also had drawbacks, making financial life difficult for many of the roughly 4 million U.S. citizens living abroad. Unlike most countries, the U.S. taxes citizens on income earned both at home and abroad. Often expatriates were stunned to find they could be considered tax cheats under the expansive U.S. law and that compliance would be onerous.

In reaction, more than 25,000 expats have given up U.S. citizenship since 2008, with some paying a stiff exit tax. Others are working to get Congress to change the taxation of nonresidents.

For expats and others, the IRS now offers a compliance program with lesser penalties, or none, for offshore-account holders who didn’t willfully cheat. About 65,000 taxpayers have entered the program, and the IRS says it will remain open for now.

Current and would-be tax cheats should take seriously the IRS’s vow to keep pursuing secret offshore accounts, says Bryan Skarlatos, a criminal tax lawyer with Kostelanetz & Fink who has handled more than 1,500 offshore disclosures to the IRS.

Although the IRS’s staffing is way down, he says, the agency and the Justice Department have far better tools for detecting and combating evasion than 10 years ago.

Newsletter Sign-up

Among these agencies’ tools are the Fatca law, which requires foreign firms to report information on American account holders. This law is providing the IRS with streams of useful information it’s using in prosecutions. This week brought the first guilty plea for a violation of Fatca rules by a former executive of a bank in Hungary and the Caribbean.

The IRS is also mining data from foreign bank settlements and whistleblower information. The payment of $104 million to UBS whistleblower Bradley Birkenfeld, apparently the largest ever, has inspired other informers.

To detect clusters of cheats, U.S. officials now can use a “John Doe summons” to force firms to release information on a class of customers suspected of evading taxes—even if their identities aren’t known, and even if the information isn’t in the U.S.

This strategy has been so successful that the IRS has broadened its use to identify possible tax cheats using cryptocurrencies.

“More than ever, there’s no place to hide,” says Mr. Skarlatos.

Write to Laura Saunders at laura.saunders@wsj.com

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20190415/041519parisfire_4/041519parisfire_4_167x94.jpg]](wsj_fatca_2018_files/041519parisfire_4_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20190415/041519notredame1/041519notredame1_167x94.jpg]](wsj_fatca_2018_files/041519notredame1_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20190411/041119assange4/041119assange4_167x94.jpg]](wsj_fatca_2018_files/041119assange4_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20190415/041519elevatorfff/041519elevatorfff_167x94.jpg]](wsj_fatca_2018_files/041519elevatorfff_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20190411/040519utahsuicide3/040519utahsuicide3_167x94.jpg]](wsj_fatca_2018_files/040519utahsuicide3_167x94.jpg)