Cave v. Mills.

IN THE COURTS OF EXCHEQUER AND EXCHEQUER

CHAMBER

Original Eng. Rep. version, PDF

Original Citation: (1862) 7 H & N 913

English Reports Citation: 158 E.R. 740

Feb. 27, 1862.

S. C 31 L. Ex. 265, 8 Jur. (N. S.) 363; 10 W. R.

471; 6 L T. 650.

740

CAVE V. MILLS 7H&N 914

Bramwell, B., Wilde, B., and Channell, B.,

concurred. Rule discharged. (a)

Cave 1/2.

Mills. Feb. 27, 1862. - The plaintiff was surveyor to the trustees of certain

turnpike roads It was his duty to make all contracts, and pay the amounts due,

for labour and materials required for the repair of the roads, he being

permitted to draw on the treasurer to a certain amount His expenditure was not

strictly limited to that amount, and in the yearly accounts, which it was his

duty to present to the trustees, a balance was generally claimed as due to him

and was carried to the next year's account He rendered accounts for the years

1856, 1857 and 1858, shewing certain balances due to himself. These accounts

were audited, examined and allowed by the trustees at their general annual

meeting and a statement, based on them, of the revenue and expenditure of the

trust, was published as required by the 3 Geo 4, c 126, s. 78 The trustees,

believing the accounts correct, paid off with monies in hand a portion of their

mortgage debt. The plaintiff afterwards claimed a larger sum in respect of

payments which had in fact been made by him, and which he ought to have brought

into the accounts of the above years, but knowingly omitted. The plaintiff also

rendered an account for the year 1859, which, on inquiry by the trustees, he

stated did not include all the payments, and he subsequently rendered another

account for that year in which he claimed a larger sum as due to him. - Held :

First, that the plaintiff was estopped from recovering the sums omitted in the

accounts for the years 1856, 1857 and 1858, since the trustees had acted upon

the faith that those accounts were true : Per Pollock, C. B , Channell, B , and

Wilde, B Bramwell, B., dissentaente. - Secondly, that the plaintiff was

entitled to recover the sums omitted in the account for 1859, since it was not

accepted by the trustees as true : Per totam Curiam.

This was an

action against the trustees for carrying into execution the 53 Geo. .3, c. 133

(local and personal), who were sued in the name of their cleik, for money

payable to [914] their surveyor for work and materials, &c The cause was

referred by a Judge's order to an arbitrator, who stated the following case for

the opinion of this Court -

The

plaintiff, from the year 1855 to January 1860, was surveyor to the trustees of

the Enstone, &c., turnpike roads, at the yearly salary of 401 By verbal

arrangeÁment between the plaintiff and the trustees, it was the duty of the

plaintiff to make all contracts and give orders for labour and materials

required for the maintenance of the roads, on behalf of the trustees, and to

pay the amounts due therefor, the plaintiff being for that purpose permitted by

the trustees to " draw " on the treasurer from time to time A certain

monthly sum was fixed upon by the trustees at the commencement of each year as

the limit of the amount of such "draw" in addition to the plaintiff's

salary ; but the paramount duty of the surveyor being to maintain the roads in

efficient repair, the expenditure by the plaintiff was not strictly limited to

that amount, and in the yearly accounts, which it was the practice and duty of

the plaintiff to present to the trustees, a balance was generally claimed by

him and duly allowed by the trustees, and carried on to the next year's

account.

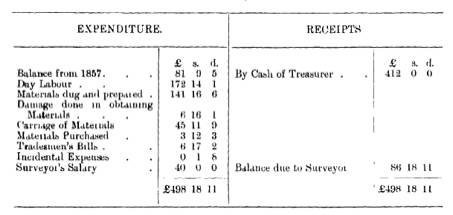

In this

manner similar accounts were rendered and allowed for the years 1856, 1857 and

1858, these accounts being entitled "An Abstract of Receipts and

Expenditure " and " Abstract of Surveyor's Expenditure," and

representing balances in the above years in favour of the plaintiff of 751. 2s

lid., 811. 9s 5d. and 861. 18s. lid. respectively.

[915] The

plaintiff presented these accounts at the general annual meeting of the

trustees, held in the month of January, and these accounts were audited and

examined by or on behalf of the trustees and compared with vouchers produced

for the payments, and the accounts were duly allowed, and a minute of the fa,ct

of allowance was duly made

(a) Repoited

by W. Marshall, Esq

7

H a H. 918. CATE V. MILLS 741

In pursuance

of the Act, 3 Geo 4, c 126, s 78, the defendant, as clerk to the trustees,

annually made out and transmitted to the clerk of the peace, after approval

thereof by the trustees, a statement of the debts, revenues, and expenditure

received or incurred on account of the trust. This statement, so far as

respected the expenditure on the roads, was based upon the above mentioned

accounts rendered by the plaintiff as surveyor, although not always strictly

following them.

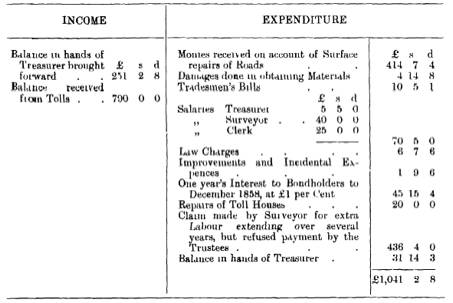

The

following are copies of the plaintiff's account for 1858, and of the statement

for the same year subsequently returned by the trustees to the clerk of the

peace, and which statements were duly published as tequired by law.

Enstons,

Heyfotcl Bridge, Bicester, Weston on the Green, and Kirthngton

Turnpike

Roads.

Abstract of

Surveyor's Expenditure for 1858.

[916]

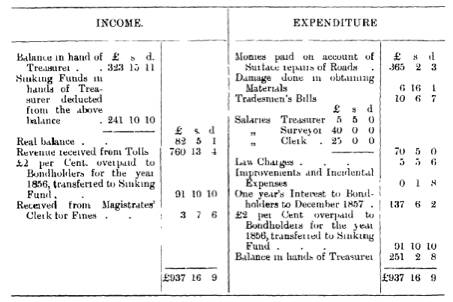

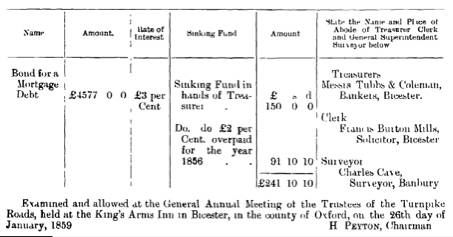

General

Statement of t he Income and Expenditure of the Enstons, Heyford Bridge,

Bicester, Weston on the Green, and Kirtlington Turnpike Roads, betwee, the 1st

day of January and t he 31st day of December, 1858, both inclusive --

742

CAVE V. MILLS 7 H & N 917

[917]

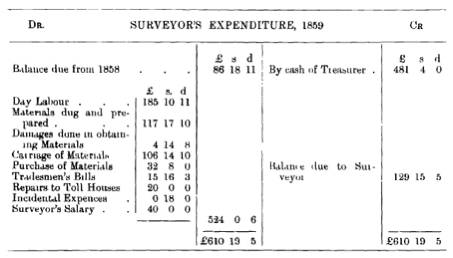

At the

General Annual Meeting of the Trustees in January, 1860, the plaintiff rendered

the following Account for the year 1859 .-

.

In answer to

an inquiry by the trustees, the plaintiff then informed them that the above

account did not include the whole of the payments made by him, and that there

were other outstanding claims. The following minute was made in the trustees'

book :-" The surveyor's account for the first year was examined, when

there appeared to be a balance due to him of 1291. 15s. 5d."

The meeting

was adjourned, and at the adjourned meeting the plaintiff rendered an account

claiming 4361. 4s. as due to him, instead of the above mentioned balance of

1291. 15s. 5d.

In

consequence of an intimation from the trustees the plaintiff resigned his

situation aa surveyor.

The

following account for 1859 was subsequently returned to the clerk of the

peace:-

7 S. &

N. US. CAVE 0. MILLS 743

[918]

General

Statement of the Income and Expenditure of the Enstons (&c.) TurnÁpike

Roads, between 1st day of January and the 31st day of December 1859.

In the

general statement at the foot, it appears that the mortgage debt of the trust

had been reduced by the sum of 2281. 17s., the amount of three bonds paid off

during the year.

In the

statement of the year 1860, sent to the clerk of the peace after the present

action was commenced, the sum of 4281. 3s. lid is stated to be " retained

in treasurer's hands to meet the claim of Mr. Cave, late surveyor, to be tried

at the Oxon March Assizes, 1861."

The

plaintiff, before the commencement of this action, had in fact made payments to

the amount of 2201. in respect of '.labour and materials reasonably necessary

for and done, and expended in, the repairs of the roads during the years 1856,

1857, 1858 and 1859, in excess of the amount included in his accounts as

originally rendered to the trustees for ths [919] above years; and there are

besides still outstanding claims by third persons to a considerable amount in

respect of work and materials for the roads done and supplied in the above

years, under verbal orders and directions given by the plaintiff as surveyor,

and which last mentioned outstanding claims are not within the present action

or order of reference.

The above

sum of 2201. consisted in part of balances paid by the plaintiff after he

rendered his account for 1859, for monies due to labourers and others, for work

and materials during the above years, and on account of which they had been

paid monies by the plaintiff from time to time.

The whole

amount ought to have been paid and brought into the accounts of the above

years, but was knowingly omitted by the plaintiff, partly from negligence and

partly to avoid complaint by the trustees, and to keep the apparent expenditure

as low as possible, and in the expectation that the trust funds would in future

years be better Èble to afford the outlay necessary for the maintenance of the

roads and the paymeit of former arrears, and there was no actual fraud

contemplated by the plaintiff.

Neither the

defendant nor the trustees had any notice or knowledge or means of knowledge of

these outstanding debts or claims, but on the contrary they believed, and the

plaintiff intended they should believe, that the accounts rendered by him to

them included all the debts and liabilities incurred by him in respect of the

repairs of the said roads to the close of each year, and such accounts were

acted upon by the trustees as above mentioned.

744

CAVE V. MILLS 7 H & N 920

The

pleadings and local acts of parliament are to be referred to, if necessary, as

part of the case.

The question

for the opinion of the Court is, whether the plaintiff is entitled at law to

recover the whole or any part of the said sum of 2201

[920] If the

Court should be of opinion that the plaintiff is entitled to recover the said

sum of 2201., then I (the arbitrator) find and award that the defendant, as

such clerk as aforesaid, is indebted to the plaintift in the sum of 2681 Gs

(being the said sum of 2201. added to the balance of the plaintiff's claim of

1291. 15s 5d in his last account, beyond the amount paid into Court), and

judgment is, to he entered for that sum.

If the Court

should be of opinion that the plaintiff is entitled in law to recover the

amount actually paid by him in respect of tepairs for the year 1859 only, as

disÁtinguished from the previous years, then I find and award that the

defendant, as such clerk, is indebted to the plaintiff in the sum oi 1031. 6s

(being one-fourth of the said sum of 2201. added to the above mentioned

balance, beyond the amount paid into Court), and judgment is to be entered for

that sum.

But if the

Court should be of opinion that the plaintiff is not entitled to recover any

part of the said sum of 2201., then I find and award that the defendant, as such

clerk, is indebted to the plaintiff in the sum of 481. 6s. beyond the amount

paid into Court, and judgment is to be entered for that sum.

Hayes,

Serjt. (A. S. Hill with him), argued for the plaintiff (a) By the 3 Geo. 4, c.

126, s. 78, the trustees of every turnpike load are requited, at their general

annual meeting in each year, to examine, audit and settle the accounts of their

treasurers, clerks and surveyors; and when the accounts shall be settled and

allowed by the trustees, they shall be signed by the chairman, and if any

treasurer, clerk or surveyor, shall refuse or neglect to produce his accounts,

he shall be dealt with according to the provisions with regard to officers

refusing to account, and when the accounts shall [921] be audited, allowed and

signed, the clerk to the trustees shall make out a statement of the debts,

revenue, and expenditure received or incurred on account of the trust, which

shall be submitted to the trustees, and when approved by the majority shall be

signed by the chairman; and the clerk shall, within thirty days, transmit the

same to the clerk of the peace of the county in which the road to which the

statement relates shall lie. The 7th section requires the clerk of the peace to

cause the statement to be produced to the Quarter Sessions, and to be

registered. There is no estoppel. An estoppel must be mutual; here it would not

be. When, indeed, a person wilfully makes a false statement, with the intention

that another should act upon it, and he does so to his prejudice, the former is

precluded from contesting its truth: Picard v. Sears (6 A. & E. 469),

Freeman v. Cooke (2 Exch. 654) But here the trustees have not been prejudiced

by the accounts rendered by the defendant. On the contrary, they have been

benefited, for they have had a larger balance in hand, and have been enabled to

pay off some bond debts The authorities on this subject are collected in

Smith's Lead Cas vol. 2, p. 334, 4th ed. Skynng v. Greenwood (4 B. & C.

281) is distinguishable There, the paymasters of a military corps had given

credit in account to an officer for increased pay, to which they knew he was

not entitled, and for more than four years they allowed him to draw upon the

faith that the money belonged to him; so that their conduct was equivalent to a

voluntary payment with full knowledge of the facts. [Channell, B. In Shaw v.

Picton (4 B & C. 715), the agent of the grantor and grantee of an annuity

delivered an account to the grantee, by which it appeared that the agent had

received certain payments on account of the annuity, which had not in fact been

received, and it was held that the agent was [922] bound by the account which

he had delivered, unless he could shew that he had given credit for those

payments by mistake.] That decision proceeded upon the same principle as

tiki/ring v. Cheenwood (4 B. & C 281) [Wilde, B At the bottom of the

account for 1858, is. "Examined and allowed at the General Annual Meeting

of the trustees," and it is signed by the chairman, as credited and

settled. Then, can the surveyor, after that, claim items not included in it-]

Unless a statement in an account that money has been received, which has not in

fact been received, differs from the suppression of a claim, Shaw v. Pidwi is

in point. [Channell, B., referred to Lucas v. Oldham (Moo. & R. 293).]

Suppose a person has a claim for 5001,

(a) In last

Michaelmas Term, Nov. 18 and 22.

7

H & N 921 CAVE 17. MILLS 745

and omits to include it in an account delivered,

can the debtor say, "I have Imd out the money and made a profit of it, and

therefore you are estopped from recovering it back'?" [Channell, B. The

arbitrator finds that the omission was designedly made.] In Heane v. Rogers (9

B. & C. 577, 586), Bayley, J., in delivering the judgÁment of the Court,

said : "There is no doubt, but that the express admissions of a paity to

the suit, or admissions implied from his conduct, are evidence, and strong

evidence against him , but we think, that he is at Liberty to prove that such

admissions were mistaken, or were untrue, and is not estopped or concluded by

them, unless another person has been induced by them to alter his condition; in

such a case the patty is estopped from disputing their truth with respect to

that person (and those claiming under him), and that transaction; but as to

third persona he is not bound " [Wilde, B Suppose a servant is directed to

make certain disbursements, and he does it in an extravagant manner, and then

says that he has disbursed far less than he really has, can he after some years

say, " I disbursed more, pay me the difference 1"] There is no

estoppel unless the [923] other party is prejudiced by the misrepresentaÁtion

With respect to the account for the year 1859, there is clearly no estoppel,

for that account was not accepted by the trustees, and another was substituted

by the plaintiff.

Melhsh

(Sawyer with him). The plaintiff from time to time delivered accounts to the

trustees, in which he wilfully omitted large disbursements, and upon the faith

of those accounts the trustees have dealt with the trust money in a way which

they aught not and could not have done if true accounts had been rendered, for

they have made public returns of a balance in hand, with which they have paid

off debts. The arbitrator has found that no fraud was in fact contemplated by

the plaintiff, but that means that there was no pecuniary dishonesty, for he

has done that which, in point of law, is a fraud, for he has made a wilfully

false statement with the intention to deceive. It resembles the case of

directors of a joint stock Company publishing false accomnts, in which case an

action of deceit will lie. The case therefore falls within the principle of

Pward v. Sears (6 A & E. 469). [Wilde, B The trustees are bound every year

to examine, audit, and settle the accounts, which must be signed by the

chairman as correct, but if a surveyor can at his own pleasure pass any

accounts, the audit is wasted.] The expenses ought to be paid out of the

receipts of the current year, but the effect of these accounts is to make them

payable in a manner not conÁtemplated by the statute. If a steward for the

space of four or five years, rendered accounts in which disbursements were

omitted, could he, upon its being discovered, recover the money ] [Bramwell, B

Whete a person has paid money with full knowÁledge of the facts, he cannot

recover it back, that, how-[924]-ever, is the ca.se of a person seeking to undo

that which he has deliberately and intentionally done But, suppose a butcher

sent in his account week by week arid was paid it, if, at the end of a

twelvemonth, he sent in a supplementary bill, that would not be undoing

anything which he had done, but the simple omission to bring some items into

account The case of an agent may be different, because there is a legal duty to

render a, correct account.] The position of the trustees has been altered by

reason of the false account rendered by the plaintiff After the accounts have

been examined, audited and signed, the trustees are bound to print copies and

transmit them to each of the trustees and to one of the Secretaries of State,

who is to cause abstracts to be kid before Parliament. .3 Geo 4, c. 126, ss.

78, 80 , 3 & 4 Wm 4, c. 80, ss. 1, 5. The market value of turnpike bonds is

legulated by these accounts, the trustees of the roads are trustees for the

shareholders; they are empowered to form a sinking fund, and when it amounts to

2001., they must apply it in discharge of the monies borrowed by paying the

creditors willing to accept the lowest composition . 12 & 13 Viet c. 87, s.

3; 13 & 14 Viet c 79, a. 4. The trustees are prejudiced, because the etteof

of publishing false accounts is to make the affairs of the trust appear in a

better condition than they really are, and consequently the trustees would be

obliged to purchase their bonds at a higher rate. The plaintiff may have

intended to take upon himself the outstanding liabilities and not to charge the

trustees, if so, these would be honest accounts ; but if he intended, from some

motive of his own, to suppress for a time those liabilities, and to charge the

trustees with them in some future yeai, they would be dishonest accounts. As

against him, it must be assumed that they are honest accounts. [Wilde, B. The

maxim applies: "Allegans contraiia non est audiandus/' Broom's Maxims, p.

160, 161, 3rd ed ] Skyi ing v [925] G-reemuooii

Ex. Div.

xiv.-24*

746

CAVE V. MILLS 7 H & N 924.

(4 B. &

C. 281), S&aw v. Ptcfo1/2 (4 B. & C. 715), and Freeman v Cook (2 Exch.

654), are authorities in point.

Hayes,

Serjt, replied.

Cur. adv.

vult.

The learned

Judges having differed in opinion, the following judgments were now delivered.

Wilde, B.

The judgment which I am about to deliver, is that of the Lord Chief Baron, my

hi other Channell and myself.

This was a

special case stated by an arbitrator for our opinion

We consider

that the question intended to be submitted to us by the arbitrator is, ˜whether

he ought, as arbitrator, to give effect to the evidence of the plaintiff in

referÁence to the omitted items. He finds the evidence to be true, but leaving

to us to determine whether the plaintiff is to be entitled to the benefit of it

It has been contended that he was not so entitled by reason of his own conduct

as found and stated in the case by the arbitrator.

It was

broadly laid down, in Shaw v Picion (4 B. & C. 729), that "if an agent

(employed to receive money, and bound by his duty to his principal fiom time to

time to communicate to him whether the money is received or not) rendeis an

account from time to time, which contains a statement that the money is received,

he is bound by that account, unless he can shew that that statement was made

unintentionally and by mistake. If he cannot shew that, he is not at liberty

afterwards to say that the money had not been received, and never will be

received, and to claim leimbursement in respect of those sums for which he had

previously given [926] credit," and the Court went on to say, that "

when an agent has deliberately and intentionally comÁmunicated to a principal

that the money due to him has been received, he makes the communication at his

peril, and is not at liberty afterwards to lecover the money back again "

In that case, his agent's intentional statement was, that ceitain monies

properly stood to his principal's credit, whereas the present case involves

only a stateÁment equally intentional (but probably with a worse motive), that

the expenses to which his principal was liable were restricted to certain sums

by him stated.

The effect

of the one statement was to swell the credit side of the account, that of the

other to diminish the debit side.

In either

case the balance would be equally affected, the principal equally deceived, and

led to act upon the false statement to his prejudice.

The case of

Skyrvng v. Greenwood, in the same book, proceeds upon a similar view of the

law. The Court there treated a credit intentionally given by the agent, with

full knowledge of the facts, as standing on the same footing with money

voluntarily paid. And as the one could not be recovered back, so the other

could not be set oft.

And in like

manner, in Denby v. Mao-re (1 B. & Aid 123), the Court held that a tenant

who had for some years paid the land tax, and knowing he was entitled to deduct

it from his rent had not done so, could not recover it from his landlord.

Another general

principle of law was invoked by the defendants in the present ease.

And it was

argued, that the plaintiff having made a statement false to his own knowledge,

upon which the defendants acted, was bound by such statement.

The case

finds that it was the " practice and duty " of [927] the plaintiff to

render the accounts in question, and that the " defendants believed,"

as the plaintiff intended they should, " that the accounts were

true," and contained all the items to which the plaintiff was entitled.

And further,

that the defendants thereupon "allowed" the accounts as required by

the statute, and in further

pursuance of the statute, transmitted to the clerk of the peace a statement of

the debts, revenue and expenditure of the trust, baaed upon the accounts so

rendered by the plaintiff.

It is also

obvious that these false accounts were put forward by the plaintiff for (ear

his expenditure should be thought extravagant.

It is

equally obvious that he had his own objects in avoiding a conclusion to that

effect in the minds of the trustees, and it can not be doubted that he

anticipated dismissal, or some action on their part, if they knew the truth,

which, however beneficial to the trust they administered, would be prejudicial

to him

He intended

that the trustees, being kept in ignorance of the truth, should act differently

from what they would have done had they known the truth. And it was

7

H & N. 928. CAVE V. MILLS 747

contended, upon this state of circumstances,

that the trustees who settled, allowed, and adopted the accounts so rendered,

" acted " upon them within the meaning of the word " acted

" in that rule of law.

We are of

opinion that both these principles apply to the present case. Indeed they are

but variations of one and the same broad principle, that a man shall not be

allowed to blow hot and cold-to affirm at one time and deny at another-making a

claim on those whom he has deluded to their disadvantage, and founding that

claim on the very matters of the delusion Such a principle has its basis in common

sense and common justice, and whether it is called " estoppel," or by

any other name, it is one which [928] Courts of law have in modern times most

usefully adopted. We are therefore of opinion that the arbitrator ought not to

find for the plaintiff in respect of the sums kept out of the accounts for the

years before 1859.

But they do

not apply to the accounts for 1859; and for the sums really and properly

expended by the plaintiff in that year we are of opinion that he ought to

recover.

Bramwell, B.

In this case, it will be convenient to state the facts, to shew how I

appreciate them. The plaintiff was surveyor of a turnpike road, the trustees of

which, sued in the name of their clerk, are the defendants. As such surveyor,

it was his duty to find and pay for labour and materials for the repair of the

road He did so, and received from time to time payments on account for the

defendants. It was also his duty to render an account to the trustees, of the

payments he made and the sums he received. This is found as a fact, and indeed

is shewn by his having done so; and it was not only necessary as a matter of

account and means of settling between him and them, but also in order to enable

them to make and render accounts as required by the statute. He accordingly

rendered an account of the years 1856, 1857 and 1858, in which he stated

various payments he had made, the amount of his salary, and, on the other side,

gave credit for cash received, shewing ceitain balances due to himself. These

accounts were received by the defendants in the belief that they were correct,

and treated as such in the returns they were obliged by statute to make, that

is to say, they stated they had laid out the sums he mentioned for labour and

materials. In point of fact, he had laid out more. He afterwards tendered

another account for the year 1859, but, on being challenged as to its

correctness, he acknowledged it was not correct, and stated he had laid out

more, and claimed payment thereof, and of the items omitted in former years. This

[929] second account was not received by the defendants in the belief it was

correct, nor treated as such in their returns, as they mentioned therein the

sum named in the account, and also the additional sum claimed, adding they had

refused payment of it.

This action

was brought to recover the omitted items. It was referred to arbitration, and

the arbitrator has found, that it was the plaintiff's paramount duty to keep

the roads in efficient repair, that

though a certain monthly sum was fixed as the limit, the plaintiff might

draw on the treasurer, the plaintiff was not strictly limited to that amount

for his outlay, and that he had in fact, in excess of the sums mentioned in the

accounts, made payments to the amount of 22U1. in respect of labour and materials

seasonably necessary for, and done and expended in the repair of the roads

during the years 1856, 1757, 1858 and 1859 I take it, therefore, that the

arbitrator finds that had the plaintiff rendered just accounts, he would have

been entitled to receive that amount from the trustees , that is to say, that

at one time he had a cause of action against them for money paid to that

amount. Now, these accounts were untrue; they directly, indeed, asserted

nothing untrue, but they meant that the amounts mentioned m them had been, and

alone had been, expended and incurred in the respective years, and I think it

makes no difference, that part of the sums he claimed were in fact paid after

the account for 1859 was rendered, because I take it that the accounts mean

that the monies mentioned in them are all that have been paid or are payable.

The

arbitrator further finds that the whole amount ought to have been brought into

the accounts of the above years, but was knowingly omitted by the plaintiff

partly through negligence, partly to avoid complaints from the trustees, and in

expectation of their being in better funds in future years, and the arbitrator

adds, " there was no actual fraud, in fact, [930] contemplated by the

plaintiff." If this means, as I understand, that he did not intend to put

more money in his pocket than was due to him, or that he did not think he was

committing a fraud, I am content so to take

748

CAVE V. MILLS 7 H & N

931.

it. But if it means that no fraud was committed,

then, with sincere respect for the arbitrator, I dissent. Without lading down

any more sweeping proposition, I think it may be safely said, that where, as

here, there is a duty to tell the truth, and no duty or obligation the other

way (which it might be said, would be when one sought to buy poison to murder

another), and an untruth is told to the knowledge of the teller, for his own

purposes, and the statement is accepted as true, a fraud is committed If fraud,

then, makes any difference, I think it exists The questions are, can the

plaintiff recover for the years 1856, 1857, 1858 and 1859, or if not, for the

last or for none '

Now, if the

defendants have any right, as against the plaintiff in consequence of these

incorrect accounts, it must be in respect of some duty from him to them. For

the question here is not whether he shall be punished, but what are his duties

and their rights. Now, his duty was the duty of every one who undertakes

anything, viz., to bring honesty and reasonable skill and care to its

performance. Having undertaken then to render accounts, he was bound to render

them honestly, and with reasonable skill and care, not with absolute accuracy,

but with no defect arising from fraud or negligence. The duty of care was as

great as the duty of honesty, and negligence as much a breach of duty as fraud

in the rendering of the accounts. The trustees, therefore, ought to have the

aame right against the plaintitt if the incorrectness of the accounts had

proceeded from carelessness as from fraud. If Skynng v. Greenwood proves

anything, it proves that. If one can suppose such a case as that there were

certain items that ought not to be charged, but he thought they ought, and

fraudulently suppressed them, they would have no right [931] against him This

shews that fraud of itself gives no right-it is inaccuracy, and that gives them

rights whether it proceeds from fraud or negligence. But can it be said that

.my negligence in the accounts, however gross, would cause the plaintiff to

lose his debt, and forfeit his cause of action once existing, or estop him from

shewing the truth 1 It is to be remembered that these accounts are but

statements. Would an inaccurate verbal statement of the amount due, the

inaccuracy proceeding from fraud or negliÁgence, and there being a duty to be

honest and caieful, have this effect' It seems to me that it would not. It is

not for me to give reasons for this, it is for those who assert that the

plaintiff has lost his right of action to give reasons why it should be so It

is not to punish him, as I have said. Besides, even for punishment such a law

as the defendants allege would be unreasonable, because, the punishment would

not depend on the gravity of the offence, but on the importance of the

subject-matter of it. Thus, the most dishonest suppression of a farthing in the

account would be followed by the loss of a farthing only; the most venial

suppression of 10001. would be followed by the loss of that amount Nor is it

necessary so to decide such a case to do justice to the defendants If, by the

falsity of the account, they have sustained damage, tbey may maintain an action

and recover a sum equal to that damage, and not, as here, make a gain by the

transaction. Again, the maxim " Allegans suam turpitudinem nou est

audiendus" cannot apply. The plaintiff does not allege his turpitude, it

is the defendants who do. The plaintiff alleges he paid this money,- he did so

The defendants say, you have rendered an incorrect account, and done so

fraudulently ; he admits the former statement, and denies the latter. How can

he then be said to set it up as his cause of action, which is what the maxim

means"? Nor does the other maxim, "Allegans contrana uon est

audiendus" apply. The plaintiff does not allege " contrana,"

[932] which I take it, means at the same time doing in fact what is popularly

called " blow hot and cold."

Nor is the

case within the rule, that if a man makes a statement with intent another shall

act on it, and the other does act on it, the first shall never, against the

second, be permitted to deny it, for here there is no evidence the account has

been acted on. It was said, I believe by myself, that this account was acted on

as much as an account can be, that is to say, it was accepted as tiue, but if

so, it seems to me that such a case cannot be within the rule On examination of

that rule it will be found that it supposes a case where, if the plaintiff

could deny his former statement and recover, the defendant would lose precisely

what the plaintiff would gain, which would not be the result in such cases as

this That is to say, if a horse is bought on a representation by A. it does not

belong to him, and afterwards A. sues the buyer for the horse, if he recovered,

the buyer would lose precisely what A.

7

H & N 933. ATKINSON

V. DENBY 749

reovered,

and the damage done by the falsity

would be to the amount of that recovery , that is not so here.

Nor do I

think those cases apply in which it has been held that money, voluntarily paid

with the knowledge of the facts, cannot be recovered back. There an act has

been done which it is sought to undo, then as much is to be taken out of the

defendant's pocket as is to be put into the plaintiffs. The various authorities

cited, with the exception of Skyrmg v. Greenwootl, are instances of the

application of those rules to which I have addressed myself. In Shaw v. Pidon

the money had been paid over, and that is relied on in the judgment. That case,

however, requires notice. As I have said, if it proves anything it shews that

the plaintiff could not recover, whether the inaccuracy of his accounts proceeded

from fraud or negligence It is undoubtedly an authority very much in favour of

the defendant's argument, but it is distinguishable. Part of the money in [933]

that case sought to be set oft' (which is the same as recovered) by the

defendants, had actually been paid, and though the residue had not been

specifically paid, the account had continued , and if the presumption is good,

that the first payment out is against the first payment in, the balance also had

been paid out. I am aware that the reasons given are not baaed on this, but the

fact is not lost sight of, and even if it had been, it would only shew the case

was the common one of a right judgment with wrong reasons If I thought it in

point, I should acquiesce, but I do not, and certainly think it ought not to be

extended It seems to me, that this reasoning also furnishes an answer to a

question, put, I believe, also by myself : " Suppose if the account had

shewn a balance against the plaintiff and he had paid it over, could he have

recovered it back 1 " First, in the case supposed, an act would have been

done , secondly, it is not clear that the plaintiff would be seeking to recover

back money by demanding payment of items brought forward anew. Another way of

putting this difficulty has occurred to me, viz., "Suppose the plaintiff

had wrongly charged his side of the account and overestimated his receipts, and

paid over a balance 2" The case is not very probable, but here also an act

would be done, viz., the money paid over.

In the

result then, I think the burthen on the defendants , that they have brought

forward neither principle nor authority to justify us in holding that the

plaintiff has lost a cause of action he once had , that the tenor of the authorities

is the other way -I mean those which hold that the statement must be acted on,

or the position of the one party changed in order to bind the other (see Sanden

on v. Collnmti) (4 Man. & C4. 209) t and the principle also applies by

which a bare promise to give a chattel or do anything would not bind, while the

gift itself and the act when done would. It seems to me also a great mischief

would be mtiocluced if a man might say, " I [934] owed you money and have

not paid you, but you said, carelessly, I had, so now I will not pay."

I think,

therefore, the plaintiff entitled to recover for all the years, but as to the

year 1859, I think it clear on the defendants' own reasoning, as to that year

the account was not accepted as true ; the fraud then was not committed, only

attempted ; the inaccuracy was corrected , the defendants never could have

maintained any action for breach of duty as to the accounts rendered for 1859.

It seems to me that the plaintiff is entitled to judgment for his whole claim,

clearly for the year 1859

Judgment

accordingly