[*90]

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE

YEAR 1995

30 June 1995

CASE CONCERNING EAST TIMOR

(PORTUGAL v. AUSTRALIA)

Treaty of 1989

between Australia and Indonesia concerning the “Timor Gap.”

Objection that

there exists in reality no dispute between the Parties — Disagreement

between the Parties on the law and on the facts — Existence of

a

legal dispute.

Objection that

the Application would require the Court to determine the

rights and obligations of a third State in the absence of

the consent of that State

— Case concerning Monetary Gold

Removed from Rome in 1943 — Question

whether the Respondents objective conduct is separable from the conduct of

a

third State.

Right of peoples

to self-determination as right erga omnes and essential principle of

contemporary international law — Difference between erga omnes

character of a norm and rule of consent to jurisdiction.

Question whether

resolutions of the General Assembly and of the Security

Council constitute “givens” on the content of which the Court would

not have to

decide de novo.

For the two

Parties, the Territory of East Timor remains a non-self-governing territory and

its people has the right to self-determination.

Rights and

obligations of a third State constituting the very subject-matter of the

decision requested The Court cannot exercise the jurisdiction

conferred

upon it by the declarations made by the Parties under Article 36. paragraph

2,

of its Statute to adjudicate on the dispute referred to it by the

Application.

JUDGMENT

Present:

President Bedjaoui; Vice-President Schwebel; Judges Oda, Sir Robert Jennings, Guillaume, Shahabuddeen,

Aguilar-Mawdsley,

Weeramantry, Ranjeva, Herczegh, Shi, Fleischhauer, Koroma,

Vereschchetin;

Judges ad hoc Sir Ninian Stephen, Skubniszewski;

Registrar Valencia-Ospina.

[*91]

In the case

concerning East Timor,

between

the

Portuguese Republic,

represented

by

H.E.

Mr. Ant-nio Cascais, Ambassador of the Portuguese Republic to

the

Netherlands,

as

Agent;

Mr.

José Manuel Servulo Correia, Professor in the Faculty of Law of

the

University of Lisbon and Member of the Portuguese Bar,

Mr.

Miguel Galvao Teles, Member of the Portuguese Bar,

as

Co-Agents, Counsel and Advocates;

Mr.

Pierre-Marie Dupuy, Professor at the University Panthéon-Assas

(Paris 11)

and Director of the Institut des hautes études internationales of

Paris,

Mrs.

Rosalyn Higgins, Q.C., Professor of international Law in the University of

London, as Counsel and Advocates;

Mr.

Rui Quartin Santos, Minister Plenipotentiary, Ministry of Foreign

Affairs, Lisbon,

Mr.

Francisco Ribeiro Telles, First Embassy Secretary, Ministry of

Foreign

Affairs, Lisbon, as Advisers;

Mr.

Richard Meese, Advocate, Partner in Frere Cholmeley, Paris,

Mr.

Paulo Canelas de Castro, Assistant in the Faculty of Law of the University of

Coïmbra,

Mrs.

Luisa Duarte, Assistant in the Faculty of Law of the University of

Lisbon,

Mr.

Paulo Otero, Assistant in the Faculty of Law of the University of Lisbon,

Mr.

lain Scobbie, Lecturer in Law in the Faculty of Law of the University

of

Dundee, Scotland,

Miss

Sasha Stepan, Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, Counsellors at Law,

Prague,

as

Counsel;

Mr.

Fernando Figueirinhas, First Secretary, Portuguese Embassy in

the

Netherlands, as Secretary,

and

the Commonwealth of

Australia,

represented by

Mr.

Gavan Griffith, Q.C., Solicitor-General of Australia,

as

Agent and Counsel;

H.E.

Mr. Michael Tate, Ambassador of Australia to the Netherlands,

former

Minister of Justice,

Mr.

Henry Burmester, Principal International Law Counsel, Office of

Inter-

national Law, Attorney-General’s Department,

as

Co-Agents and Counsel;

[*92]

Mr.

Derek W. Bowett, Q.C., Whewell Professor emeritus, University of Canibridge,

Mr.

James Crawford, Whewell Professor of International Law, University of

Cambridge,

Mr.

Alain Pellet, Professor of International Law, University of Paris X Nanterre

and Institute of Political Studies, Paris,

Mr.

Christopher Staker, Counsel assisting the Solicitor-General of Australia,

as

Counsel;

Mr.

Christopher Lamb, Legal Adviser, Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and

Trade,

Ms

Cate Steams, Second Secretary, Australian Embassy in the Netherlands,

Mr.

Jean-Marc Thouvenin, Head Lecturer, University of Maine and Institute of

Political Studies, Paris,

as

Advisers,

The Court,

composed as above,

after deliberation,

delivers the

following Judgment:

1. On 22 February

1991, the Ambassador to the Netherlands of the Portuguese Republic (hereinafter

referred to as “Portugal”) filed in the Registry of

the Court an Application instituting proceedings against the Commonwealth

of

Australia (hereinafter referred to as “Australia”)

concerning “certain activities

of Australia with respect to East

Timor”. According to the Application

Australia had, by its conduct, “failed to observe … the

obligation to respect

the duties and powers of [Portugal as) the administering Power (of East

Timor]

— and … the right of the people of East Timor to

self-determination and the

related rights”. In consequence, according to the Application,

Australia had

“incurred international responsibility vis-à-vis both the people of

East Timor

and Portugal”. As the basis for the jurisdiction of the

Court, the Application

refers to the declarations by which the two States have accepted the

compulsory jurisdiction of the Court under Article 36, paragraph 2, of its

Statute.

2. In accordance

with Article 40, paragraph 2, of the Statute, the Applica

tion was communicated

forthwith to the Australian Government by the

Registrar; and, in accordance with paragraph 3 of the same Article, all

the

other States entitled to appear before the Court were notified by the

Registrar

of the Application.

3. By an Order

dated 3 May 1991, the President of the Court fixed 18 November 1991 as the

time-limit for filing the Memorial of Portugal and 1 June 1992

as the time-limit for filing the Counter-Memorial of Australia, and those

pleadings were duly filed within the time-limits so fixed.

4. In its

Counter-Memorial, Australia raised questions concerning the jurisdiction of the

Court and the admissibility of the Application. In the course of a

meeting held by the President of the Court on I June 1992 with the Agents

of

the Parties, pursuant to Article 31 of the Rules of Court, the Agents

agreed that

these questions were inextricably linked to the merits and that they

should

therefore be heard and determined within the framework of the merits. [*93]

5. By an Order

dated 19 June 1992, the Court, taking into account the agreement of the Parties

in this respect, authorized the filing of a Reply by Portugal

and of a Rejoinder by Australia, and fixed I December 1992 and 1 June

1993

respectively as the time-limits for the filing of those pleadings. The

Reply was

duly filed within the time-limit so fixed. By an Order of 19 May 1993, the

President of the Court, at the request of Australia, extended to 1 July 1993

the time-

limit for the filing of the Rejoinder. This pleading was filed on

5 July 1993.

Pursuant to Article 44, paragraph 3, of its Rules, having given the other

Party

an opportunity to state its views, the Court considered this filing as valid.

6. Since the Court

included upon the Bench no judge of the nationality of

either of the Parties,

each Party proceeded to exercise the right conferred by

Article 31, paragraph 3, of the Statute to choose a judge ad hoc to sit in

the

case; Portugal chose Mr. Antonio de Arruda Ferrer-Correia and Australia

Sir

Ninian Martin Stephen. By a letter dated 30 June 1994, Mr.

Ferrer-Correia

informed the President of the Court that he was no longer able to sit, and,

by

a letter of 14 July 1994, the Agent of Portugal informed the Court that its

Government had chosen Mr. Krzysztof Jan Skubiszewski to replace him.

7. In accordance

with Article 53, paragraph 2, of its Rules, the Court, after

ascertaining the views of the Parties, decided that the pleadings and

annexed

documents should be made accessible to the public from the date of the

open-

ing of the oral proceedings.

8. Between 30

January and 16 February 1995, public hearings were held in the

course of which the Court heard oral arguments and replies by the following:

For Portugal: H.E. Mr. Antonio

Cascais,

Mr.

José Manuel Servulo Correia,

Mr.

Miguel Galvão Teles,

Mr.

Pierre-Marie Dupuy,

Mrs.

Rosalyn Higgins, Q.C.

For Australia: Mr. Gavan Griffith,

Q.C.,

H.E.

Mr. Michael Tate,

Mr.

James Crawford,

Mr.

Alain Pellet,

Mr.

Henry Burmester,

Mr.

Derek W. Bowett, Q.C.,

Mr.

Christopher Staker.

9. During the oral

proceedings, each of the Parties, referring to Article 56,

paragraph 4, of the Rules of Court, presented documents not previously

produced. Portugal objected to the presentation of one of these by Australia,

on

the ground that the document concerned was not “part of a

publication readily

available” within the

meaning of that provision. Having ascertained Australia’s

views, the Court examined the

question and informed the Parties that it had

decided not to admit the

document to the record in the case.

*

* *

10. The Parties

presented submissions in each of their written pleadings;

in the course of the oral proceedings, the following final submissions

were

presented:

[*94]

On behalf of

Portugal,

at the hearing on

13 February 1995 (afternoon):

”

Having regard to the facts and points of law set forth,

Portugal has the

honour to

— Ask the Court to

dismiss the objections raised by Australia and to

adjudge and declare that it has jurisdiction to deal

with the Application of Portugal and that that Application is admissible, and

— Request

that it may please the Court:

(1)

To adjudge and declare that, first, the rights of the people of East

Timor to self-determination, to territorial integrity and

unity and to permanent sovereignty over its wealth and natural resources and,

secondly,

the duties, powers and rights of Portugal as the administering Power of

the

Territory of East Timor are opposable to Australia, which is under

an

obligation not to disregard them, but to respect them.

(2)

To adjudge and declare that Australia, inasmuch as in the first place

it has negotiated, concluded and initiated performance of the Agreement

of 11 December 1989, has taken internal legislative measures for the application

thereof, and is continuing to negotiate, with the State party to

that

Agreement, the delimitation of the continental shelf in the area of

the

Timor Gap; and inasmuch as it has furthermore excluded any

negotiation

with the administering Power with respect to the exploration

and exploitation of the continental shelf in that same area; and, finally,

inasmuch as it

contemplates exploring and exploiting the subsoil of the sea in the

Timor

Gap on the basis of a plurilateral title to which Portugal is not a party

(each of these facts sufficing on its own):

(a) has infringed and is

infringing the right of the people of East Timor

to self-determination, to territorial integrity and unity and its permanent

sovereignty over its natural wealth and resources, and is in

breach of the obligation not to disregard but to respect that right,

that integrity and that sovereignty;

(h) has infringed and is

infringing the powers of Portugal as the administering Power of the Territory

of East Timor, is impeding the fulfilment of its duties to the people of East

Timor and to the international

community, is infringing the right of Portugal to fulfil its responsibilities

and is in breach of the obligation not to disregard but to respect

those powers and duties and that right;

(c) is contravening

Security Council resolutions 384 and 389 and is in

breach of the obligation to accept and carry out Security

Council

resolutions laid down by the Charter of the United Nations, is disregarding

the binding character of the resolutions of United Nations

organs that relate to East Timor and, more generally, is in breach of

the obligation incumbent on Member States to co-operate in good

faith with the United Nations;

(3)

To adjudge and declare that, inasmuch as it has excluded and is

excluding any

negotiation with Portugal as the administering Power of the

Territory of East Timor, with respect to the exploration and

exploitation

of the continental shelf in the area of the Timor Gap, Australia has

failed

and is failing in its duty to negotiate in order to harmonize the

respective

rights in the event of a conflict of rights or of claims over maritime

areas.

[*95]

(4)

To adjudge and declare that, by the breaches indicated in paragraphs 2 and 3 of

the present submissions, Australia has incurred international responsibility

and has caused damage, for which it owes reparation

to the people of East Timor and to Portugal, in such form and manner

as

may be indicated by the Court, given the nature of the obligations breached.

(5)

To adjudge and declare that Australia is bound, in relation to the

people of East Timor, to Portugal and to the international community,

to

cease from all breaches of the rights and international norms referred to

in

paragraphs 1, 2 and 3 of the present submissions and in particular,

until

such time as the people of East Timor shall have exercised its right to

self-

determination, under the conditions laid down by the United Nations:

(a) to refrain from any negotiation,

signature or ratification of any agreement with a State other than the

administering Power concerning the

delimitation, and the exploration and exploitation, of the

continental

shelf, or the exercise of jurisdiction over that shelf, in the area of

the

Timor Gap;

(b) to refrain from any act relating to

the exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf in the area of the

Timor Gap or to the exercise of jurisdiction over that shelf, on the basis of

any plurilateral title to

which Portugal, as the administering Power of the Territory of East

Timor, is

not a party”;

On behalf of

Australia,

at the hearing on

16 February 1995 (afternoon):

“The

Government of Australia submits that, for all the reasons given by

it in the written and oral pleadings, the Court should:

(a) adjudge and declare that the Court lacks

jurisdiction to decide the

Portuguese claims or that the Portuguese claims arc inadmissible; or

(b) alternatively,

adjudge and declare that the actions of Australia

invoked by Portugal do not give rise to any breach by Australia of

rights under international

law asserted by Portugal.”

11. The Territory

of East Timor corresponds to the eastern part of the

island of Timor; it includes the island of Atauro, 25 kilometres to

the

north, the islet of Jaco to the east, and the enclave of Oé-Cusse

in the

western part of the island of Timor. Its capital is Dili, situated on its

north

coast. The south coast of East Timor lies opposite the north coast of

Australia, the distance between them being approximately 430 kilometres.

In the sixteenth century,

East Timor became a colony of Portugal;

Portugal remained there until 1975. The western part of the island

came

under Dutch rule and later became part of independent Indonesia.

12. In resolution

1542 (XV) of 15 December 1960 the United Nations

General Assembly recalled

“differences of views … concerning the status

of certain territories under the administrations of Portugal and Spain

and

described by these two States as ‘overseas provinces’ of the

metropolitan

[*96] State concerned”; and it also stated

that it considered that the territories

under the administration of Portugal, which were listed therein

(including

“Timor and dependencies”) were non-self-governing

territories within the

meaning of Chapter XI of the Charter. Portugal, in

the wake of its “Carnation Revolution”, accepted this

position in 1974.

13. Following

internal disturbances in East Timor, on 27 August 1975

the Portuguese civil and military authorities withdrew from the

mainland

of East Timor to the island of Atauro. On 7 December 1975 the

armed

forces of Indonesia intervened in East Timor. On 8 December 1975

the

Portuguese authorities departed from the island of Atauro, and thus

left

East Timor altogether. Since their departure, Indonesia has occupied

the

Territory, and the Parties acknowledge that the Territory has

remained

under the effective control of that State. Asserting that on 31 May

1976

the people of East Timor had requested Indonesia “to accept East Timor

as an integral

part of the Republic of Indonesia”, on 17 July 1976 Indonesia enacted

a law incorporating the Territory as part of its national territory.

14. Following the

intervention of the armed forces of Indonesia in the

Territory and the withdrawal of the Portuguese

authorities, the question of

East Timor became the subject of two resolutions of the Security

Council

and of eight resolutions of the General Assembly, namely, Security Council

resolutions 384 (1975) of 22 December 1975 and 389 (1976) of 22 April

1976, and General Assembly resolutions 3485 (XXX) of 12 December

1975, 31/53 of 1 December 1976, 32/34 of 28 November 1977, 33/39 of

13 December 1978, 34/40 of 21 November 1979, 35/27 of II November

1980, 36/50 of 24 November 1981 and 37/30

of 23 November 1982.

15. Security

Council resolution 384 (1975) of 22 December 1975 called

upon “all States to respect the territorial integrity of East Timor

as well

as the inalienable right of its people to self-determination”;

called upon

“the Government of Indonesia to withdraw without

delay all its forces

from the Territory”; and further called upon

“the

Government of Portugal as administering Power to co-operate

fully with the United Nations so as to enable the people of East

Timor to

exercise freely their right to self-determination”.

Security Council resolution

389 (1976) of 22 April 1976 adopted the same

terms with regard to the right of the people of East Timor to

self-determination; called upon “the Government of Indonesia to

withdraw without

further delay all its forces from the Territory”; and further called

upon “all

States and other parties concerned to co-operate fully with the

United

Nations to achieve a peaceful solution to the existing situation . .

General Assembly

resolution 3485 (XXX) of 12 December 1975 referred

to Portugal “as the administering Power”; called upon it

“to continue to

make every effort to find a solution by peaceful means”; and “strongly

deplore[d] the military

intervention of the armed forces of Indonesia in

[*97] Portuguese Timor”. In resolution 31/53

of I December 1976, and again in

resolution 32/34 of 28 November 1977, the General Assembly rejected

“the

claim that East Timor has been incorporated into Indonesia,

inasmuch as the people of the Territory have not been able to exercise freely

their right to self-determination and independence”.

Security Council

resolution 389 (1976) of 22 April 1976 and General

Assembly resolutions 31/53 of

1 December 1976, 32/34 of 28 November

1977 and 33/39 of 13 December 1978 made no reference to Portugal as

the administering Power. Portugal is so described, however, in

Security

Council resolution 384 (1975) of 22 December 1975 and in the other

resolutions of the General Assembly. Also, those resolutions which did

not

specifically refer to Portugal as the administering Power recalled

another

resolution or other resolutions which so referred to it.

16. No further

resolutions on the question of East Timor have been

passed by the Security Council since 1976 or by the General Assembly

since 1982. However, the Assembly has maintained the item on its

agenda

since 1982, while deciding at each session, on the recommendation of

its

General Committee, to defer consideration of it until the following

session. East Timor also continues to be included in the list of

non-self-

governing territories within the meaning of Chapter XI of the Charter;

and the Special Committee on the Situation with Regard to the Implementation

of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial

Countries and Peoples remains seised of the question of East Timor.

The

Secretary-General of the United Nations is also engaged in a

continuing

effort, in consultation with all parties directly concerned, to

achieve a

comprehensive settlement of the problem.

17. The

incorporation of East Timor as part of Indonesia was recognized by Australia dc

facto on 20 January 1978, On that date the Australian Minister for Foreign

Affairs stated: “The Government has made

clear publicly its opposition to the Indonesian intervention and has

made

this known to the Indonesian Government.” He added: “[Indonesia’s]

control is

effective and covers all major administrative centres of the territory.” And further:

“This is a reality with which we must come to terms. Accordingly,

the Government has decided that although it remains critical of the

means by which integration was brought about it would be unrealistic to

continue to refuse to recognize de facto that East Timor is

part of Indonesia.”

On 23 February 1978

the Minister said: “we recognize the fact that East

Timor is part of Indonesia, but not the means by which this was

brought

about”.

[*98] On 15 December 1978 the Australian Minister for

Foreign Affairs declared that negotiations which were about to begin between

Australia

and Indonesia for the delimitation of the continental shelf between Australia

and East Timor, “when they start, will signify de jure recognition

by Australia of the Indonesian incorporation of East Timor”; he

added:

“The acceptance of this situation does not alter the opposition

which the

Government has consistently expressed regarding the manner of incorporation.” The negotiations in question began in

February 1979.

18. Prior to this,

Australia and Indonesia had, in 1971-1972, established a delimitation of the

continental shelf between their respective

coasts; the delimitation so effected stopped short on either

side of the

continental shelf between the south coast of East Timor and the

north

coast of Australia. This undelimited part of the continental shelf

was

called the “Timor Gap”.

The delimitation

negotiations which began in February 1979 between

Australia and Indonesia

related to the Timor Gap; they did not come to

fruition. Australia and Indonesia then turned to the possibility of

establishing a provisional arrangement for the joint exploration and

exploitation of the resources of an area of the continental shell A Treaty to

this

effect was eventually concluded between them on 11 December 1989, whereby a

“Zone of Cooperation”

was created “in an area between the

Indonesian Province of

East Timor and Northern Australia”. Australia

enacted legislation in 1990 with a view to implementing the Treaty;

this

law came into force in 1991.

*

* *

19. In these

proceedings Portugal maintains that Australia, in negotiating and concluding

the 1989 Treaty, in initiating performance of the

Treaty, in taking

internal legislative measures for its application, and in

continuing to negotiate with Indonesia, has acted unlawfully, in that

it

has infringed the rights of the people of East Timor to

self-determination

and to permanent sovereignty over its natural resources,

infringed the

rights of Portugal as the administering Power, and contravened

Security

Council resolutions 384 and 389. Australia raised objections to the

jurisdiction of the Court and to the admissibility of the Application. It took

the position, however, that these objections were inextricably linked

to

the merits and should therefore be determined within the framework of

the merits. The Court heard the Parties both on the objections and on

the

merits. While Australia concentrated its main arguments and

submissions

on the objections, it also submitted that Portugal’s case on the

merits

should be dismissed, maintaining, in particular, that its actions did not

in

any way disregard the rights of Portugal.

[*99]

*

* *

20. According to

one of the objections put forward by Australia, there

exists in reality no dispute between itself and Portugal. In another

objection, it argued that Portugal’s Application would require the

Court to

rule on the rights and obligations of a State which is not a party

to the

proceedings, namely Indonesia. According to further objections of Australia,

Portugal lacks standing to bring the case, the argument being that

it does not have a sufficient interest of its own to institute the proceedings,

notwithstanding the references to it in some of the resolutions of

the

Security Council and the General Assembly as the administering Power

of East Timor, and that it cannot, furthermore, claim any right to represent

the people of East Timor; its claims are remote from reality, and

the

judgment the Court is asked to give would be without useful effect;

and

finally, its claims concern matters which are essentially not legal in

nature

which should be resolved by negotiation within the framework of

on-

going procedures before the political organs of the United

Nations.

Portugal requested the Court to dismiss all these objections.

*

* *

21. The Court will

now consider Australia’s objection that there is in

reality no dispute between itself and Portugal.

Australia contends that

the case as presented by Portugal is artificially limited to the question

of

the lawfulness of Australia’s conduct, and that the true respondent

is

Indonesia, not Australia. Australia maintains that it is being sued

in

place of Indonesia. In this connection, it points out that Portugal

and

Australia have accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the Court

under

Article 36, paragraph 2, of its Statute, but that Indonesia has not.

In support of the

objection, Australia contends that it recognizes, and

has always recognized, the right of the people of East Timor to

self-

determination, the status of East Timor as a non-self-governing

territory,

and the fact that Portugal has been named by the United Nations as the

administering Power

of East Timor; that the arguments of Portugal, as

well as its submissions, demonstrate that Portugal does not challenge

the

capacity of Australia to conclude the 1989 Treaty and that it does

not

contest the validity of the Treaty; and that consequently there is in

reality

no dispute between itself and Portugal.

Portugal, for its

part, maintains that its Application defines the real

and only dispute submitted to the Court.

22. The Court

recalls that, in the sense accepted in its jurisprudence and that of its

predecessor, a dispute is a disagreement on a point of law

or fact, a conflict of legal views or interests between parties (see Mavrommatis

Palestine Concessions, Judgment No. 2, 1924, P.C.I J., Series

A,

No. 2, p. 11; Northern Cameroons, Judgment, LC.J Reports 1963, p. 27;

and Applicability of the Obligation to Arbitrate under Section 21 of

the

United Nations Headquarters Agreement of 26 June 1947, Advisory

[*100] Opinion, I.C.J. Reports 1988, p. 27, para.

35). In order to establish the

existence of a dispute, “It must be

shown that the claim of one party is

positively opposed by the other” (South West Africa, Preliminary Objections, Judgment, [I.C.J.

Reports 1962, p. 328); and further, “Whether

there exists an international dispute is

a matter for objective determination” (Interpretation of Peace Treaties with Bulgaria, Hungary and

Romania, First Phase, Advisory Opinion, L C.). Reports 1950, p. 74).

For the purpose of

verifying the existence of a legal dispute in the

present case, it is not

relevant whether the “real dispute” is between Portugal and Indonesia rather than Portugal and

Australia. Portugal has,

rightly or wrongly, formulated complaints of fact and

law against Australia which the latter has denied. By virtue of this denial,

there is a legal

dispute.

On the record

before the Court, it is clear that the Parties are in disagreement, both on the

law and on the facts, on the question whether the

conduct of Australia in negotiating, concluding and initiating performance

of the 1989 Treaty was in breach of an obligation due by Australia

to Portugal under international law.

Indeed,

Portugal’s Application limits the proceedings to these questions.

There nonetheless exists a legal dispute between Portugal and Australia. This

objection of Australia must therefore be dismissed.

*

* *

23. The Court will

now consider Australia’s principal objection, to the effect that

Portugal’s Application would require the Court to determine

the rights and obligations

of Indonesia. The declarations made by the

Parties under Article 36, paragraph 2, of the Statute do not include

any

limitation which would exclude Portugal’s claims from the

jurisdiction

thereby conferred upon the Court. Australia, however, contends

that the jurisdiction so conferred would not enable the Court to act if, in

order to

do so, the Court were required to rule on the lawfulness of

Indonesia’s

entry into and continuing presence in East Timor, on the validity of the

1989

Treaty between Australia and Indonesia, or on the rights and obligations of

Indonesia under that Treaty, even if the Court did not have to determine its

validity. Portugal agrees that if its Application required the

Court to decide any of these questions, the Court

could not entertain it.

The Parties disagree, however, as to whether the Court is required

to

decide any of these questions in order to resolve the dispute referred to it,

24. Australia

argues that the decision sought from the Court by Portugal would inevitably

require the Court to rule on the lawfulness of the

conduct of a third State, namely Indonesia, in the absence of that

State’s

consent. In support of its argument, it cites the Judgment in the case

concerning Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943, in which the

Court

ruled that, in the absence of Albania’s consent, it could not take

any deci-[*101]-sion on the international

responsibility of that State since “Albania’s

legal interests would not only be affected by a decision, but would

form

the very subject-matter of the decision” (I.C.J. Reports 1954, p. 32).

25. In reply,

Portugal contends, first, that its Application is concerned

exclusively with the objective conduct of Australia, which consists

in

having negotiated, concluded and initiated performance of the

1989

Treaty with Indonesia, and that this question is perfectly separable

from

any question relating to the lawfulness of the conduct of

Indonesia.

According to Portugal, such conduct of Australia in itself

constitutes a

breach of its obligation to treat East Timor as a non-self-governing territory

and Portugal as its administering Power; and that breach could be

passed upon by the Court by itself and without passing upon the rights

of

Indonesia. The objective conduct of Australia, considered as such,

constitutes the only violation of international law of which Portugal

complaint.

26. The Court

recalls in this respect that one of the fundamental prin-

ciples of its Statute is that it cannot decide a dispute between States

with-

out the consent of those States to its jurisdiction. This principle

was

reaffirmed in the Judgment given by the Court in the case concerning

Monetary

Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 and confirmed in several of

its subsequent decisions (see Continental

Shelf (Libyan Arab Jamahiriya/Malta), Application for Permission to Intervene,

Judgment, I.C.J. Reports

1984, p. 25, para. 40; Military and Paramilitary

Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of

America), Jurisdiction and

Admissibility, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1984, p. 431, para. 88;

Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali), Judgment, I.C.J. Reports

1986,

p. 579, para. 49; Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute

(El

Salvador/Honduras), Application to Intervene, Judgment, I.C.J.

Reports

1990, pp. 114-116, paras. 54-56, and p. 112, para. 73; and Certain

Phosphate Lands in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia), Preliminary Objections,

Judgment, (I.C.J. Reports 1992, pp. 259-262, paras. 50-55).

27. The Court notes

that Portugal’s claim that, in entering into the

1989 Treaty with Indonesia, Australia violated the obligation to

respect

Portugal’s status as administering Power and that of East Timor as

a

non-self-governing territory, is based on the assertion that

Portugal

alone, in its capacity as administering Power, had the power to

enter into

the Treaty on behalf of East Timor; that Australia disregarded this exclusive

power, and, in so doing, violated its obligations to respect the status

of Portugal and that of East

Timor.

The Court also

observes that Australia, for its part, rejects Portugal’s

claim to the exclusive power to conclude treaties on behalf of East

Timor,

and the very fact that it entered into the 1989 Treaty with

Indonesia

shows that it considered that Indonesia had that power. Australia

in substance argues that even if Portugal had retained that power, on

whatever

basis, after withdrawing from East Timor, the possibility existed that

the

power could later pass to another State under general international

law,

[*102]

and that it did so pass to Indonesia; Australia affirms moreover that,

if

the power in question did pass to Indonesia, it was acting in

conformity

with international law in entering into the 1989 Treaty with that

State,

and could not have violated any of the obligations Portugal

attributes to

it. Thus, for Australia, the fundamental question in the present case

is

ultimately whether, in 1989, the power to conclude a treaty on behalf

of

East Timor in relation to its continental shelf lay with Portugal or

with

Indonesia.

28. The Court has

carefully considered the argument advanced by

Portugal which seeks to separate Australia’s behaviour from that

of

Indonesia. However, in the view of the Court, Australia’s behaviour

cannot be assessed without first entering into the question why it is

that

Indonesia could not lawfully have concluded the 1989 Treaty, while Portugal

allegedly could have done so; the very subject-matter of the Court’s

decision would necessarily be a determination whether, having regard to the

circumstances in which Indonesia entered and remained in East

Timor, it could or could not have acquired the power to enter into treaties on

behalf of East Timor relating to the resources of its continental

shelf. The

Court could not make such a determination in the absence of

the consent of Indonesia.

29. However,

Portugal puts forward an additional argument aiming

to show that the principle formulated by the Court in the case concerning Monetary

Gold Removed from Rome in 1943 is not applicable in

the present case. It maintains, in effect, that the rights which

Australia

allegedly breached were rights erga omnes and that

accordingly Portugal could require it, individually, to respect them regardless

of whether or

not another State had conducted itself in a similarly

unlawful manner.

In the

Court’s view, Portugal’s assertion that the right of peoples

to

self-determination, as it evolved from the Charter and from United

Nations practice, has an erga

omnes character, is irreproachable. The

principle of self-determination of peoples has been recognized by

the

United Nations Charter and in the jurisprudence of the Court (see

Legal

Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South

Africa in Namibia (South West Africa)

notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), Advisory Opinion,

I.C.J. Reports 1971, pp. 31-

32, paras. 52-53; Western Sahara,

Advisory Opinion, [CJ. Reports

1975, pp. 31-33, paras. 54-59); it

is one of the essential principles of contemporary international law.

However, the Court considers that the erga

omnes character of a

norm and the rule of consent to jurisdiction are two

different things. Whatever the nature of the obligations invoked,

the

Court could not rule on the lawfulness of the conduct of a State when

its

judgment would imply an evaluation of the lawfulness of the conduct

of

another State which is not a party to the ease. Where this is so,

the

Court cannot act, even if the right in question is a right erga

omnes.

[*103]

30. Portugal

presents a final argument to challenge the applicability to the present case of

the Court’s jurisprudence in the case concerning Monetary Gold

Rernoved from Rome in 1943. It argues that the principal matters on which its

claims are based, namely the status of East Timor as a

non-self-governing territory and its own capacity as the

administering

Power of the Territory, have already been decided by the General Assembly and

the Security Council, acting within their proper spheres of competence; that in

order to decide on Portugal’s claims, the Court might

well need to interpret those decisions but would not have to decide de

novo on their content

and must accordingly take them as “givens”; and

that consequently the Court is not required

in this case to pronounce on

the question of the use of force by Indonesia in East Timor or upon

the

lawfulness of its presence in the Territory.

Australia objects

that the United Nations resolutions regarding East

Timor do not say what Portugal claims

they say; that the last resolution

of the Security Council on East Timor goes back to 1976 and the

last

resolution of the General Assembly to 1982, and that Portugal takes

no

account of the passage of time and the developments that have taken

place since then;

and that the Security Council resolutions are not reso-

lutions which are binding under Chapter VII of the Charter or

otherwise

and, moreover, that they are not framed in mandatory terms.

31. The Court notes

that the argument of Portugal under consideration rests on the premise that the

United Nations resolutions, and in particular those of the Security Council,

can be read as imposing an obligation on States not to recognize any authority

on the part of Indonesia

over the Territory and, where the latter is

concerned, to deal only with

Portugal. The Court is not persuaded, however, that the relevant resolutions

went so far.

For the two

Parties, the Territory of East Timor remains a non-self-

governing territory and its people has the right to self-determination.

Moreover, the General Assembly, which reserves to itself the right

to

determine the territories which have to be regarded as

non-self-governing

for the purposes of the application of Chapter XI of the Charter,

has

treated East Timor as such a territory. The competent subsidiary

organs

of the General Assembly have continued to treat East Timor as such to

this day. Furthermore, the Security Council, in its resolutions 384

(1975)

and 389 (1976) has expressly called for respect for “the

territorial integrity of East Timor as well as the inalienable right of its

people to self-

determination in accordance with General Assembly resolution 1514

(XV)”.

Nor is it at issue

between the Parties that the General Assembly has

expressly referred to Portugal

as the “administering Power” of East

Timor in a number of the resolutions it adopted on the subject of

East

Timor between 1975 and 1982, and that the Security Council has done so

in its resolution 384 (1975). The Parties do not agree, however,

on the [*104]

legal implications that flow from the reference to Portugal as the

administering Power in those texts.

32. The Court finds

that it cannot be inferred from the sole fact that

the above-mentioned resolutions of the General Assembly and the

Security Council refer to Portugal as the administering Power of East

Timor

that they intended to establish an obligation on third States to

treat

exclusively with Portugal as regards the continental shelf of East

Timor.

The Court notes, furthermore, that several States have concluded

with

Indonesia treaties capable of application to East Timor but which do

not

include any reservation in regard to that Territory. Finally, the

Court

observes that, by a letter of 15 December 1989, the Permanent

Representative of Portugal to the United Nations transmitted to the

Secretary-

General the text of a note of protest addressed by the Portuguese

Embassy

in Canberra to the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

on the occasion of the conclusion

of the Treaty on 11 December 1989;

that the letter of the Permanent Representative was circulated, at

his

request, as an official document of the forty-fifth session of the

General

Assembly, under the item entitled “Question of East Timor”

, and of the

Security Council; and that no responsive action was taken

either by the

General Assembly or the Security Council.

Without prejudice

to the question whether the resolutions under discussion could be binding in

nature, the Court considers as a result that

they cannot be regarded as

“givens” which

constitute a sufficient basis for

determining the dispute between the Parties.

33. It follows from

this that the Court would necessarily have to rule

upon the lawfulness of Indonesia’s conduct as a prerequisite

for deciding

on Portugal’s contention that Australia violated its obligation to

respect

Portugal’s status as administering Power, East Timor’s

status as a non-

self-governing territory and the right of the people of

the Territory to

self-determination and to permanent sovereignty over its wealth

and

natural resources.

*

* *

34. The Court

emphasizes that it is not necessarily prevented from

adjudicating when the judgment it is asked to give might affect the

legal

interests of a State which is not a party to the case. Thus, in the

case

concerning Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru (Nauru v. Australia), it

stated, inter alia, as follows:

”

In the present case, the interests of New Zealand and the United

Kingdom do not constitute

the very subject-matter of the judgment

to be rendered on the merits of Nauru’s Application … In

the

present case, the determination of the responsibility of New Zealand

or the United Kingdom is not a prerequisite for the

determination of

the responsibility of Australia, the only object of

Nauru’s claim … In the present case, a finding by the Court regarding the existence or

the content of the responsibility attributed to Australia by Nauru

[*105] might well have implications for the

legal situation of the two other

States concerned, but no finding in respect of that legal situation

will

be needed as a basis for the Court’s decision on Nauru’s

claims

against Australia. Accordingly, the Court cannot decline to

exercise

its jurisdiction.”

(I.C.J Reports 1992, pp. 261-262, para. 55.)

However, in this

case, the effects of the judgment requested by Portugal would amount to a

determination that Indonesia’s entry into and

continued presence in East Timor are unlawful and

that, as a consequence, it does not have the treaty-making power in matters

relating to

the continental shelf resources of East Timor. Indonesia’s rights and

obligations would thus constitute the very subject-matter of such a

judgment

made in the absence of that State’s consent. Such a

judgment would run

directly counter to the “well-established principle of international

law

embodied in the Court’s Statute, namely, that the Court can only

exercise

jurisdiction over a State with its consent” (Monetary Gold Removed from

Rome in 1943, Judgment, LC.J Reports 1954, p. 32).

*

* *

35. The Court

concludes that it cannot, in this case, exercise the jurisdiction it has by

virtue of the declarations made by the Parties under

Article 36, paragraph

2, of its Statute because, in order to decide the claims

of Portugal, it would have to rule, as a prerequisite, on the lawfulness

of

Indonesia’s conduct in the absence of that State’s consent.

This conclusion applies to all the claims of Portugal, for all of them raise a

common

question: whether the power to make treaties concerning the

continental

shelf resources of East Timor belongs to Portugal or Indonesia,

and,

therefore, whether Indonesia’s entry into and continued

presence in the

Territory are lawful. In these circumstances, the Court does not deem

it

necessary to examine the other arguments derived by Australia from

the

non-participation of Indonesia in the case, namely the Court’s lack

of

jurisdiction to decide on the validity of the 1989 Treaty and the

effects on

Indonesia’s rights under that treaty which would result from a

judgment

in favour of Portugal.

*

* *

36. Having

dismissed the first of the two objections of Australia which

it has examined, but upheld

its second, the Court finds that it is not

required to consider Australia’s other objections and that it cannot

rule

on Portugal’s claims on the merits, whatever the importance of the

questions raised by those claims and of the rules of international law

which

they bring into play.

37. The Court

recalls in any event that it has taken note in the present

Judgment (paragraph 31) that, for the two Parties, the Territory of

East

[*106]

Timor remains a non-self-governing territory and its people has the

right

to self-determination.

38. For these

reasons,

The Court,

By fourteen votes

to two,

Finds that it cannot in

the present case exercise the jurisdiction conferred upon it by the

declarations made by the Parties under Article 36,

paragraph 2, of its

Statute to adjudicate upon the dispute referred to it by

the Application of the Portuguese Republic.

In favour: President Bedjaoui; Vice-President Schwebel; Judges Oda, Sir Robert Jennings,

Guillaume, Shahabuddeen, Aguilar-Mawdsley, Ranjeva,

Herczegh, Shi,

Fleischhauer, Koroma, Yereshchetin; Judge ad hoc Sir

Ninian Stephen;

Against: Judge Weeramantry; Judge ad hoc Skubiszewski.

Done in English and

in French, the English text being authoritative, at

the Peace Palace, The Hague, this thirtieth day of

June, one thousand

nine hundred and ninety-five, in three copies, one of which will be

placed

in the archives of the Court and the others transmitted to the Government of

the Portuguese Republic and the Government of the Common-

wealth of Australia,

respectively.

(Signed) Mohammed Bedjaoui,

President.

(Signed) Eduardo Valencia-Ospina,

Registrar.

Judges Oda, Shahahuddeen, Ranjeva and

VERE5HCHETIN append

separate opinions to the Judgment of the Court.

Judge Weeramantry and Judge ad hoc Skubiszewski append dissenting opinions

to the Judgment of the Court.

(Initialled) M.B.

(Initialled)

E.V.O.

[*107]

SEPARATE OPINION OF

JUDGE ODA

I. I voted in

favour of the Judgment because I agreed with the Court

that the Application brought by Portugal against

Australia on 22 February 1991 should be dismissed, as the Court lacks

jurisdiction to entertain

it.

However, I am

unable to subscribe to the reason given by the Court

for this finding, that is, that

”

[the Court] cannot, in this case, exercise the jurisdiction it has by virtue of

the declarations made by the Parties under Article 36, paragraph 2, of its

Statute because, in order to decide the claims of Portugal, it would have to

rule, as a prerequisite, on the lawfulness of

Indonesia’s conduct in

the absence of that States consent” (Judgment, para. 35; emphasis added.)

When it refers to

the “consent” of

Indonesia the Court itself seems to be

uncertain as to what this “consent” of Indonesia would have

meant.

Would it have meant that, in order for the Court to exercise its

jurisdiction, Indonesia would have had to have intervened in these

proceedings

or would it have meant that Indonesia would have had to have accepted

that jurisdiction under Article 36 (2) of

the Statute?

For my part, I

believe that the Court cannot adjudicate upon the

Application of Portugal for the sole reason that Portugal lacked locus

standi to bring against

Australia this particular case concerning the continental shelf in the Timor

Sea.

*

* *

2. Portugal, in its

Application, defined the dispute, on the one hand, as

”

relate[d] to the opposability to Australia:

(a) of the duties of, and delegation of

authority to, Portugal as the

administering Power of the Territory of East Timor; and

(b) of the right of the people of East

Timor to self-determination,

and the related rights (right to territorial integrity and unity

and permanent sovereignty over natural wealth and resources)”

(Application, para. 1).

On the other hand,

Australia, which did not regard Portugal as having

authority over the Territory of East Timor in the late 1980s, has only

been accused by

Portugal in its Application of having engaged in

[*108] “[the] activities … [which]

have taken the form of the negotiation and

conclusion by Australia with a third State [Indonesia] of an

agreement

relating to the exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf

in

the area of the ‘Timor Gap’ and the negotiation, currently

in progress,

of the delimitation of that same shelf with that same third

State [Indonesia]”

(Application, para. 2; emphasis added).

3. If there had

been anything for Portugal to complain about this

would not have been “the opposability” to any State of either “the

duties

of, and delegation of authority to, Portugal as the administering Power

of the Territory of East Timor”, or “the right of the

people of East Timor

to self-determination, and the related rights” (Application, para. 1).

Any

complaint could only have related to Portugal’s alleged title,

whether as

an administering Power or otherwise, to the Territory of East

Timor

together with the corresponding title to the area of continental

shelf

which would overlap with that of Australia. In this respect Portugal,

in

its Application, has given an incorrect definition of the dispute and

seems

to have overlooked the difference between the opposability to any State

of its rights and duties as the administering Power or of the rights of the

people of East

Timor and the more basic question of whether Portugal is

the State entitled to assert these rights and duties.

In particular

Portugal contends, with regard to subparagraph (b) in

the quotation in paragraph 2 above, that the right of the people of East

Timor to self-determination and the related rights guaranteed by

the

United Nations Charter to a people still under the control of a

colonial

State or of an administering Power for non-self-governing

territories

should be respected by the whole international community under

which-

ever authority and control that people may be placed. Australia has

not

challenged the “right of the people of East Timor to

self-determination,

and the related rights”. The right of that people to

self-determination and

other related rights cannot be made an issue and is not an issue of

the present case.

The present case

relates solely to the title to the continental shelf which

Portugal claims to possess as a coastal State. This point cannot be

over-

emphasized.

*

* *

4. What, then, did

Australia actually do to Portugal or the people of

East Timor? It is essential to note that, in the area of the “Timor

Gap”,

Australia has not asserted a new claim to any seabed area intruding

into

the area of any State or of the people of the Territory of East Timor,

nor

has it acquired any new seabed area from any State or from that

people

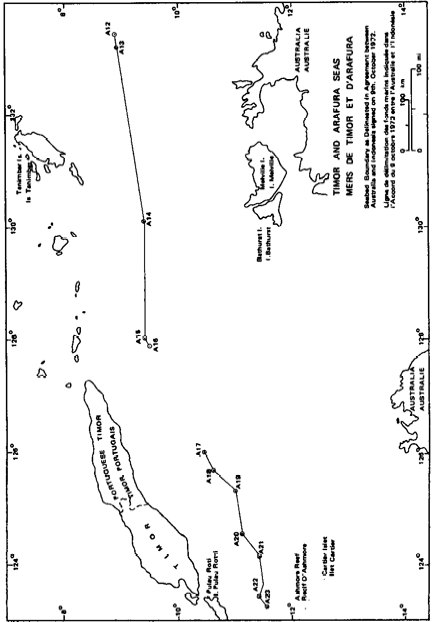

(see sketch-map on page 109).

[*109]

Sketch-map

N.B.

The

area with cross-hatching shows the location of the Zone of Cooperation under

the 1989 Treaty and also gives a general idea of the “Timor

Gap”.

[*110] In fact,

Australia’s original title to the continental shelf in the

“Timor

Gap” cannot be

challenged at all by any State or by any people. Under

the contemporary

rules of international law, Australia is entitled ipso jure

to its own continental shelf in the southern part of the Timor Sea —

but

at the same time a State which has territorial sovereignty over

East

Timor, and which lies opposite to Australia at a distance of roughly

250

nautical miles, has the title with respect to the continental shelf off

its

coast in the northern part of the “Timor Gap” (see sketch-map: vertical

hatching). How far each continental shelf extends is determined

not in

geographical terms but by the legal concept of the continental shelf.

The

continental shelves to which both States are thus entitled

overlap

somewhere in the middle of the “Timor Gap”. Just as in the

cases con-

templated by Article 6 (I) of the 1958 Convention on the

Continental

Shelf and by Article 83(1) of the 1982 United Nations Convention on

the

Law of the Sea, Australia should have negotiated with the coastal

State

lying opposite to it across the Timor Sea (see sketch-map: State X

as

indicated therein) and did indeed negotiate with that State with respect

to

the overlapping continental shelves.

5. A

recital of the events which have taken place since the 1970s in

relation to the delimitation of the continental shelf in the relevant

areas

can usefully be given at this stage.

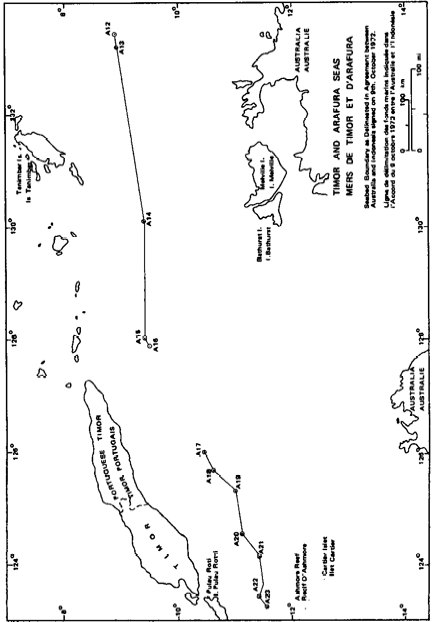

Pursuant

to the Agreement “establishing certain seabed boundaries”

(United Nations, Treaty Series, Vol. 974, p. 307), Australia and Indonesia

drew a line of delimitation east of longitude 133Á 23’ E in the

Arafura

Sea on 18 May 1971 - in the area between Australia, on the one hand,

and West Irian (Indonesian territory on the island of New Guinea) and

Aru Island (Indonesian territory), on the other. On 9 October 1972

the

same two Governments, acting under the Agreement “establishing

certain seabed boundaries in the area of the Timor and Arafura seas,

supplementary to the Agreement of 18 May 1971” (United Nations, Treat;

Series, Vol.

974, p. 319) (NB. the Chart attached to this Agreement is

reproduced on page Ill of this opinion), defined other lines of

delimitation west of longitude 133° 23’ E extending to longitude 127°

56’ E in the

area of the Timor and Arafura seas between Australia, on the one hand,

and the Tanimbar Islands

(Indonesian territory), on the other. Another

line was drawn westward from longitude 126° 00’ E. This latter

agreement, however, left open a gap of nearly 120 nautical miles between

these

two lines off the coast of “Portuguese Timor” (as it is called on a

chart

attached to the Agreement), which was commonly known as the

“Timor

Gap”.

At that

time Portugal did not, however, attempt to negotiate with

Australia on the delimitation of the continental shelf in the area

thus

left open for Portugal’s benefit by the 1972 Agreement

between Indonesia

and Australia. This certainly leads one to question whether Portugal

did,

at that time, deem itself to be in the position of a coastal State with sov-[*111]

Chart Attached to

the Agreement of 9 October 1972

[*112]-ereignty over the

eastern part of the island of Timor (East Timor) and

whether it in fact thought that it could claim a title to the

continental

shelf in the “Timor Gap”.

Instead

of dividing the area by drawing a boundary, as in the case of

the 1971 and 1972 Agreements with Indonesia as explained above, Australia

agreed in the 1989 Treaty with Indonesia “on the Zone of Cooperation

in an area between the Indonesian Province of East Timor and

northern

Australia” to constitute

a “Zone of Cooperation”. The content

of the 1989 Treaty — what was gained and lost in the “Timor

Gap” both

by Australia and by the State lying opposite to it (see sketch-map:

State

X as indicated therein) — cannot be disputed, as the Treaty

was drawn

up with the consent of the States concerned.

6.

Indonesia had apparently claimed since the 1970s the status of a

coastal State for the Territory of East Timor, considered to be one of

its

provinces (as explained in paragraph 13 below), and, as such, had

negotiated with the opposite State, Australia, on the overlapping part of

their

respective continental shelves. On that basis, Australia concluded in

1989

a treaty with Indonesia which would remain in force for an initial

40-year

term and successive terms of 20 years unless the two States agreed

other-

wise (Art. 33) (Application, Ann. 2, text of the Treaty annexed to

the

Petroleum Act, 1990). If Portugal had claimed the status of a coastal State,

whether as administering

Power of the non-self-governing Territory or

otherwise, and had thus claimed the corresponding title to the continental

shelf in the northern part of the “Timor Gap” extending southward

from the coast of East Timor, then Portugal could

and should have initiated a dispute over that title with Indonesia which had

made a similar

claim. The party with which Portugal should have engaged in a dispute

over the conflicting titles to the continental shelf in the northern part

of

the “Timor Gap”

(see sketch-map: vertical hatching) could only have been Indonesia.

A

dispute could have turned on which of the two States, Indonesia

or

Portugal, was a coastal State located on the Territory of East Timor

and

thus was entitled to the continental shelf extending southwards from

the

coast of the Territory of East Timor, thus meeting the continental shelf

of

Australia in the middle of the “Timor Gap”. This is the

dispute in relation to which Portugal could have instituted proceedings against

Indonesia on the merits. However, any issue concerning the seabed area of

the

“Timor Gap”

could not have been the subject-matter of a dispute between

Portugal and Australia unless

and until such time as Portugal had been

established as having the status

of the coastal State entitled to the corresponding continental shelf (in other

words, Portugal would have to be

designated as State X, see sketch-map).

7. If

Portugal was the coastal State with a claim to the continental

shelf in the “Timor

Gap” (see sketch-map:

vertical hatching), then the

Treaty which Australia concluded with Indonesia in 1989 would

certainly

[*113] have

been null and void from the outset. Alternatively, if Indonesia was

the coastal State, and thus had a right

over the relevant area of the continental shelf (see sketch-map: vertical

hatching), then Portugal quite

simply had no right to bring this case. In order to do so, Portugal

would

have had to have been a coastal State lying opposite to Australia.

In

order to entertain the Application against Australia with respect to

the continental shelf in the “Timor Gap” or, more specifically, the

area

called the “Zone of Cooperation” which Australia claims in part,

the

Court needs to be convinced, as a preliminary issue, of the standing

of

Portugal in this case as being a coastal State with a claim to the continental

shelf in the Timor Sea as of 1991, the year of the Application

(see

sketch-map: State X as indicated therein).

As I

repeat, an issue on which Portugal could have initiated a dispute

would have been its own entitlement to the continental shelf off the

coast

of East Timor, but could not have related to the competence of

Australia

to conclude a treaty with Indonesia.

*

* *

8. The

present Judgment, in my view, seems to rely heavily on the jurisprudence of the

case concerning Monetary Gold Removed from Rome in 1943

(1954). That case does not seem to be relevant to the

present case as the Court found in 1954 that “[t]o go into the merits

of

[questions which relate to the lawful or unlawful character of

certain

actions of Albania vis-ö-vis Italy]” in a case brought by Italy against

France, among other co-Respondents, “would

be to decide a dispute

between Italy and Albania” and that “[t]he Court cannot

decide such a

dispute without the consent of Albania” (I.C.J. Reports 1954, p. 32). In

that case “Albania’s

legal interests would not only be affected by a decision [of the Court], but

would form the very subject-matter of the decision” (ibid.).

The

present case is quite different in nature. The dispute does not

relate to whether Indonesia, the third State, was entitled in principle

to

conclude a treaty with Australia, but rather the subject-matter of

the

whole case relates solely to the question of whether Portugal or Indonesia, as

a State lying opposite to Australia, was entitled to the continental shelf in

the “Timor Gap”. This could have been the subject of

a

dispute between Portugal and Indonesia, but cannot be a matter in

which

Portugal and Australia can be seen to be in dispute with Indonesia as

a

State with “an interest of a legal nature which may be

affected”.

9. East

Timor was under Portuguese control from the sixteenth century onwards and the

Constitution of Portugal of 1933 stated that the

territory of Portugal comprised East Timor in Oceania. East Timor

kept

[*114] the

status of an overseas territory of Portugal even after the war, in contrast to

Indonesia which gained its independence from the Netherlands.

There is no doubt that, prior to 1974, Portugal had sovereignty over

East

Timor as one of its own overseas provinces and that Portugal, as

the

coastal State, would have had a right to the continental shelf in the seabed areas off the coast of East Timor in the Timor Sea.

10. On

the other hand, the United Nations Charter contains a “declaration

regarding non-self-governing territories” (Chap. XI) under which

Member States which have or assume responsibilities

for the administration of the colonial territories, accept as a sacred trust

the obligation to

promote the well-being of the inhabitants of these territories and, to

this

end, to transmit regularly to the Secretary-General statistical and other

information

of a technical nature relating to the territories. Portugal

never supplied regular information on its own colonies scattered

through-

out the world and was not seen to have acknowledged that those

colonies

had the status of non-self-governing territories under the United

Nations

system.

In 1960

the United Nations General Assembly, after having made the

“Declaration on Decolonization” proclaiming the right of all peoples

to

self-determination (resolution 1514 (XV)), adopted a resolution addressed

in particular to Portugal in which it considered East Timor to be a

non-

self-governing territory within the meaning of Chapter XI of the

Charter

and requested Portugal to transmit to the Secretary-General information

on East Timor,

among other non-self-governing territories under Portuguese control (resolution

1542 (XV)).

11.

Between 1961 and 1973 the General Assembly repeatedly appealed

to Portugal to comply with the decolonization policy of the United

Nations and continued to condemn Portugal’s

colonial policy and its persistent refusal to carry out that United Nations

policy. In 1963 the Security Council for its part deprecated the attitudes of

the Portuguese Government and its repeated violations of the principles of the

Charter,

urgently calling upon Portugal to implement the decolonization

policy (resolutions 180 (1963) and 183 (1963)), and in 1965 once again passed

a

resolution deploring Portugal’s failure to comply with the previous

General Assembly and Security Council resolutions (resolution 218

(1965)).

In 1972, the Security Council repeated its condemnation of the persistent

refusal of Portugal to implement the earlier resolutions (resolutions

312

(1972) and 322 (1972)).

Portugal

did not take any steps to assume the duties and responsibilities of a governing

authority in relation to those territories which should

have been treated as non-self-governing territories in accordance with

the

United Nations concept, and continued to regard them merely as

its

overseas provinces.

[*115] 12. Following the “Carnation

Revolution” in April

1974, the Government in Portugal was replaced by a new régime. The

“Law of 27 July

1974”, promulgated by the Council of State, revised the old

Portuguese

Constitution and acknowledged the right to self-determination

— including independence — of the territories under

Portuguese administration. The new Government of Portugal convened conferences

on decolonization in May 1975 in Dili and in June 1975 in Macao, to which it

invited

the representatives of several East Timorese political groups. The

“Law

of 17 July 1975”

relating to the decolonization of East Timor, which

resulted from those conferences,

was intended to put an end to the sovereignty of Portugal over East Timor in

October 1978.

On the

other hand Indonesia, which seems not to have sought previously to annex East

Timor to its own territory and had maintained

friendly relations with Portugal, appears to have begun considering

the

annexation of East Timor in the 1970s. In July 1975, the President

of

Indonesia asserted that East Timor would not be competent to attain

its

independence. The political group UDT, which supported the approach

of the Indonesian Government, organized a coup d’état

on Il August

1975. The local government in East Timor did not receive any

effective

assistance from Portugal itself; its members left in August 1975 for

the

island of Atauro north of Timor and, in December 1975, moved away

from that island

and thus left the area. Portugal did not accept the

request of the FRETILIN group to return to East Timor and Indonesia

began to prepare for a large-scale military invasion of the

Territory.

These developments marked the end of Portuguese rule in East Timor.

13. On

28 November 1975 FRETILIN declared the full independence

of the Territory and the establishment of the Democratic Republic of

East Timor. On the other hand, some other political parties, such as

UDT and APODETI, which considered that it would be difficult

for East

Timor to maintain its independence, were willing to be annexed by Indonesia

and on 30 November 1975 the representatives of those groups made

a declaration of the separation of the Territory from Portugal and

its

incorporation into Indonesia.

In

early December 1975 Indonesia sent an army of 10,000 men to Dili.

On 17 December 1975, the pro-Indonesian parties declared the establishment of

a provisional government of East Timor in Dili. Responding to

an alleged appeal from the people of East Timor, Indonesia

passed a law

on 15 July 1976 providing for annexation, which the President of Indonesia

signed on 17 July 1976. East Timor was thus given the status of

the

twenty-seventh province of Indonesia. The Portuguese authorities,

which

had already left the island, have never returned to East Timor since

that

time.

*

* *

14. As

from the year 1974, which was marked by the change in Portuguese colonial

policy under the new régime, the General Assembly con-[*116]-tinued

to adopt successive resolutions on the implementation of the Declaration on

Decolonization. In its 1974 resolution, the General Assembly

welcomed the acceptance by the new Government of Portugal of the

principle of self-determination and independence and its unqualified

appli-

cability to all the peoples under Portuguese colonial domination,

calling

upon Portugal to pursue the necessary steps to ensure the full implementation

of the “Declaration on Decolonization” (resolution 3294 (XXIX)).

In 1975

the General Assembly, for the first time, adopted a resolution relating to East

Timor in which it called upon Portugal as the administering Power to continue

to make every effort to find a solution by peaceful means through talks between

the Government of Portugal and the

political parties representing the

people of Portuguese Timor; strongly

deplored the military intervention of the armed forces of Indonesia,

and

called upon Indonesia to desist from further violation of the territorial

integrity of Portuguese Timor and to withdraw without delay its

armed

forces from the Territory in order to enable the people of the

Territory

freely to exercise their right to self-determination and

independence

(resolution 3485 (XXX)).

Further

to that General Assembly resolution, the Security Council, on 22 December 1975,

deplored the intervention of the armed forces of

Indonesia in East Timor, regretting that the Government of Portugal

was not discharging fully its responsibilities as administering Power

in

the Territory under Chapter XI of the Charter, called upon Indonesia

to

withdraw all its forces from the Territory without delay, and called

upon

Portugal as administering Power to co-operate fully with the

United

Nations so as to enable the people of East Timor to exercise freely their

right

to self-determination (resolution 384 (1975)). Several months

later, on 22 April 1976, the Security Council once again passed a resolution

in which it did not refer to the responsibility of Portugal as

the

administering Power of East Timor but was only concerned with the

military intervention of Indonesia in that Territory (resolution

389

(1976)).

15. In

a resolution of 1976, the General Assembly, following the same approach as the

one adopted in the previous year, upheld the rights of

the people of East Timor and strongly

criticized the action of Indonesia

(resolution 31/53). It should be noted, however, that Indonesia’s

claim

that East Timor should be integrated into its territory was rejected

solely

in order to uphold the rights of the people of East Timor but not to

protect the rights and duties of the State of Portugal in relation to

East

Timor or the status of Portugal as the administering Power. In 1977

the

General Assembly kept to the outline of the previous year’s

resolution

(resolution 32/34); the Government of Portugal did not feature

in this

resolution at all.

In 1978

the General Assembly desisted from its rejection of Indonesia’s claim

that East Timor had been integrated. The 1978 resolution made no

[*117]

request for the withdrawal of the Indonesian military from East Timor,

but emphasized the inalienable right of the people of East Timor to

self-